-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 14

/

04-report.Rmd

411 lines (307 loc) · 18 KB

/

04-report.Rmd

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

91

92

93

94

95

96

97

98

99

100

101

102

103

104

105

106

107

108

109

110

111

112

113

114

115

116

117

118

119

120

121

122

123

124

125

126

127

128

129

130

131

132

133

134

135

136

137

138

139

140

141

142

143

144

145

146

147

148

149

150

151

152

153

154

155

156

157

158

159

160

161

162

163

164

165

166

167

168

169

170

171

172

173

174

175

176

177

178

179

180

181

182

183

184

185

186

187

188

189

190

191

192

193

194

195

196

197

198

199

200

201

202

203

204

205

206

207

208

209

210

211

212

213

214

215

216

217

218

219

220

221

222

223

224

225

226

227

228

229

230

231

232

233

234

235

236

237

238

239

240

241

242

243

244

245

246

247

248

249

250

251

252

253

254

255

256

257

258

259

260

261

262

263

264

265

266

267

268

269

270

271

272

273

274

275

276

277

278

279

280

281

282

283

284

285

286

287

288

289

290

291

292

293

294

295

296

297

298

299

300

301

302

303

304

305

306

307

308

309

310

311

312

313

314

315

316

317

318

319

320

321

322

323

324

325

326

327

328

329

330

331

332

333

334

335

336

337

338

339

340

341

342

343

344

345

346

347

348

349

350

351

352

353

354

355

356

357

358

359

360

361

362

363

364

365

366

367

368

369

370

371

372

373

374

375

376

377

378

379

380

381

382

383

384

385

386

387

388

389

390

391

392

393

394

395

396

397

398

399

400

401

402

403

404

405

406

407

408

409

410

---

title: "Simple audio classification with Keras"

output: html_document

author: "Daniel Falbel"

---

```{r setup, include=FALSE}

knitr::opts_chunk$set(echo = TRUE, eval = FALSE)

```

## Introduction

In this tutorial we will build a deep learning model to classify words. We will use [`tfdatasets`](https://tensorflow.rstudio.com/tools/tfdatasets/articles/introduction.html) to handle data IO and pre-processing, and [Keras](https://keras.rstudio.com) to build and train the model.

We will use the [Speech Commands dataset](https://storage.cloud.google.com/download.tensorflow.org/data/speech_commands_v0.01.tar.gz) which consists of 65.000 one-second audio files of people saying 30 different words. Each file contains a single spoken English word. The dataset was released by Google under CC License.

Our model was first implemented in [*Simple Audio Recognition* at the TensorFlow documentation](https://www.tensorflow.org/tutorials/audio_recognition#top_of_page) which in turn was inpired by [*Convolutional Neural Networks for Small-footprint Keyword Spotting*](http://www.isca-speech.org/archive/interspeech_2015/papers/i15_1478.pdf). There are other approaches, like [recurent neural networks](https://svds.com/tensorflow-rnn-tutorial/), [dilated (atrous) convolutions](https://deepmind.com/blog/wavenet-generative-model-raw-audio/) or [Learning from Between-class Examples for Deep Sound Recognition](https://arxiv.org/abs/1711.10282).

The model we implement here is not the state of the art for audio recognition systems, which are way more complex, but is relatively simple and fast to train.

## Audio representation

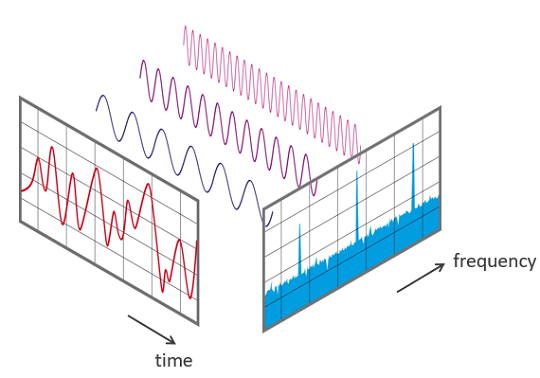

Many deep learning models are end-to-end, i.e. we let the model learn useful representations directly from the raw data but, audio data grows very fast - 16,000 samples per second with a very rich structure at many time-scales. In order to avoid raw wave sound data, researchers usually use some kind of feature engineering.

Every sound wave can be represented by it's spectrum, and digitally it can be computed using the [Fast Fourier Transform (FFT)](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Fast_Fourier_transform).

A common way to represent audio data is to break it into small chunks, which usualy overlap. For each chunk we use the FFT to calculate the magnitude of the frequency spectrum. The spectrums are then combined, side by side, to form what we call a [spectrogram](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Spectrogram).

It's also common for speech recognition systems to further transform the spectrum and compute the [Mel-Frequency Cepstral Coefficients](https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mel-frequency_cepstrum). This transformation takes into account that the human ear can't discern the difference between two closely spaced frequencies and smartly creates bins in the frequency axis. A great tutorial on MFCC's can be found [here](http://practicalcryptography.com/miscellaneous/machine-learning/guide-mel-frequency-cepstral-coefficients-mfccs/).

After this procedure, we have an image for each audio sample and we can use convolutional neural networks that are usual in image recognition models.

## Downloading

First, let's download data to a directory in our project. You can whether download from [this link](http://download.tensorflow.org/data/speech_commands_v0.01.tar.gz) (~1GB) or from R with:

```{r}

dir.create("data")

download.file(

url = "http://download.tensorflow.org/data/speech_commands_v0.01.tar.gz",

destfile = "data/speech_commands_v0.01.tar.gz"

)

untar("data/speech_commands_v0.01.tar.gz", exdir = "data/speech_commands_v0.01")

```

Inside the `data` directory we will have a folder called `speech_commands_v0.01`. The WAV audio files inside this directory are organised in sub-folders with the label names. For example, all one-second audio files of people speaking the word "bed" are inside the `bed` directory. There are 30 of them and a special one called `_background_noise_` which contains background noises that could be mixed in to simulate background noise.

## Importing

In this step we will list all audio .wav files into a `tibble` with 3 columns:

* `fname`: the file name;

* `class`: the label for each audio file;

* `class_id`: a unique integer number starting from zero for each class - used to one-hot encode the classes.

This will be useful to the next step when we will create a generator using the `tfdatasets` package.

```{r}

library(stringr)

library(dplyr)

files <- fs::dir_ls(

path = "data/speech_commands_v0.01/",

recursive = TRUE,

glob = "*.wav"

)

files <- files[!str_detect(files, "background_noise")]

df <- data_frame(

fname = files,

class = fname %>% str_extract("1/.*/") %>%

str_replace_all("1/", "") %>%

str_replace_all("/", ""),

class_id = class %>% as.factor() %>% as.integer() - 1L

)

```

## Generator

We will now create our `Dataset`, which in the context of `tfdatasets`, adds operations to the TensorFlow graph in order to read and pre-process data. Since they are TensorFlow ops, they are executed in C++ and in parallel with model training.

The generator we will create will be responsible for reading the audio files from disk, creating the spectrogram for each one and batching the outputs.

Let's start defining creating the dataset from slices of the `data.frame` with audio file names and classes we just created.

```{r}

library(tfdatasets)

ds <- tensor_slices_dataset(df)

```

Now, let's define the parameters for the spectrogram creation. We need to define the `window_size_ms` which is the size in milliseconds of each chunk we will break the audio wave; the `window_stride_ms`: the distance between the center of adjacent chunks;

```{r}

window_size_ms <- 30

window_stride_ms <- 10

```

Now we will convert the window size and stride from milliseconds to samples. We are considering that our audio files have 16,000 samples per second (1000 ms).

```{r}

window_size <- as.integer(16000*window_size_ms/1000)

stride <- as.integer(16000*window_stride_ms/1000)

```

We will obtain other quantities that will be usefull for the spectrogram creation like the number of chunks and the FFT size, ie. the number of bins the frequency axis. The function we are going to use to compute the spectrogram doesn't allow us to change the FFT size and uses by default the first superior power of 2 of the window size.

```{r}

fft_size <- as.integer(2^trunc(log(window_size, 2)) + 1)

n_chunks <- length(seq(window_size/2, 16000 - window_size/2, stride))

```

We will now use `dataset_map` which allows us to specify a pre-processing function for each observation (line) of our dataset. It's in this step that we read the raw audio file from disk and create it's spectrogram and the one-hot encoded response vector.

```{r}

# shortcuts to used TensorFlow modules.

audio_ops <- tf$contrib$framework$python$ops$audio_ops

ds <- ds %>%

dataset_map(function(obs) {

# a good way to debug when building tfdatsets pipelines is to use a print

# statement like this:

# print(str(obs))

# decoding wav files

audio_binary <- tf$read_file(tf$reshape(obs$fname, shape = list()))

wav <- audio_ops$decode_wav(audio_binary, desired_channels = 1)

# create the spectrogram

spectrogram <- audio_ops$audio_spectrogram(

wav$audio,

window_size = window_size,

stride = stride,

magnitude_squared = TRUE

)

# normalization

spectrogram <- tf$log(tf$abs(spectrogram) + 0.01)

# moving channels to last dim

spectrogram <- tf$transpose(spectrogram, perm = c(1L, 2L, 0L))

# transform the class_id into a one-hot encoded vector

response <- tf$one_hot(obs$class_id, 30L)

list(spectrogram, response)

})

```

Now, we will specify how we want batch observations from the dataset. We used `dataset_shuffle` since we want to shuffle observations from the dataset, otherwise it would follow the order of the `df` object. Then we used `dataset_repeat` in order to tell TensorFlow that we want to keep taking observations from the dataset even if all observations were already used. And most importantly here, we use `dataset_padded_batch` to specify that we want batches of size 32, but they should be padded, ie. if some observation has a different size we pad it with zeroes. The padded shapes is passed to `dataset_padded_batch` via the `padded_shapes` argument and we use `NULL` to state that this dimension doesn't need to be padded.

```{r}

ds <- ds %>%

dataset_shuffle(buffer_size = 100) %>%

dataset_repeat() %>%

dataset_padded_batch(

batch_size = 32,

padded_shapes = list(

shape(n_chunks, fft_size, NULL),

shape(NULL)

)

)

```

This is our Dataset specification, but we would need to rewrite all the code for the validation data, so it's a good practice to wrap this into a function of the data and other important parameters like the `window_size_ms` and `window_stride_ms`. Below, we will define a function called `data_geneartor` that will create the generator depending on those inputs.

```{r}

data_generator <- function(df, batch_size, shuffle = TRUE,

window_size_ms = 30, window_stride_ms = 10) {

window_size <- as.integer(16000*window_size_ms/1000)

stride <- as.integer(16000*window_stride_ms/1000)

fft_size <- as.integer(2^trunc(log(window_size, 2)) + 1)

n_chunks <- length(seq(window_size/2, 16000 - window_size/2, stride))

ds <- tensor_slices_dataset(df)

if (shuffle)

ds <- ds %>% dataset_shuffle(buffer_size = 100)

ds <- ds %>%

dataset_map(function(obs) {

# decoding wav files

audio_binary <- tf$read_file(tf$reshape(obs$fname, shape = list()))

wav <- audio_ops$decode_wav(audio_binary, desired_channels = 1)

# create the spectrogram

spectrogram <- audio_ops$audio_spectrogram(

wav$audio,

window_size = window_size,

stride = stride,

magnitude_squared = TRUE

)

spectrogram <- tf$log(tf$abs(spectrogram) + 0.01)

spectrogram <- tf$transpose(spectrogram, perm = c(1L, 2L, 0L))

# transform the class_id into a one-hot encoded vector

response <- tf$one_hot(obs$class_id, 30L)

list(spectrogram, response)

}) %>%

dataset_repeat()

ds <- ds %>%

dataset_padded_batch(batch_size, list(shape(n_chunks, fft_size, NULL), shape(NULL)))

ds

}

```

Now, we can define training and validation data generators. It's worth noting that executing this won't actually compute any spectrogram and read any file. It will only define in the TensorFlow graph how it should read and pre-process data.

```{r}

set.seed(6)

id_train <- sample(nrow(df), size = 0.7*nrow(df))

ds_train <- data_generator(

df[id_train,],

batch_size = 32,

window_size_ms = 30,

window_stride_ms = 10

)

ds_test <- data_generator(

df[-id_train,],

batch_size = 32,

shuffle = FALSE,

window_size_ms = 30,

window_stride_ms = 10

)

```

To actually get a batch from the generator we could create a TensorFlow session and ask it to run the generator. For example:

```{r}

sess <- tf$Session()

batch <- next_batch(ds_train)

str(sess$run(batch))

```

```

List of 2

$ : num [1:32, 1:98, 1:257, 1] -4.6 -4.6 -4.61 -4.6 -4.6 ...

$ : num [1:32, 1:30] 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 ...

```

Each time you run `sess$run(batch)` you should see a different batch of observations.

## Model definition

Now that we know how we will feed our data we can focus on the model definition. The spectrogram can be treated like an image, so architectures that are commonly used in image recognition tasks should work well with the spectrograms too.

We will build a convolutional neural network similar to what we have built [here](https://keras.rstudio.com/articles/examples/mnist_cnn.html) for the MNIST dataset.

The input size is defined by the number of chunks and the FFT size. Like we explained earlier, they can be obtained from the `window_size_ms` and `window_stride_ms` used to generate the spectrogram.

```{r}

window_size <- as.integer(16000*window_size_ms/1000)

stride <- as.integer(16000*window_stride_ms/1000)

fft_size <- as.integer(2^trunc(log(window_size, 2)) + 1)

n_chunks <- length(seq(window_size/2, 16000 - window_size/2, stride))

```

We will now define our model using the Keras sequential API:

```{r}

library(keras)

model <- keras_model_sequential()

model %>%

layer_conv_2d(input_shape = c(n_chunks, fft_size, 1),

filters = 32, kernel_size = c(3,3), activation = 'relu') %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2)) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 64, kernel_size = c(3,3), activation = 'relu') %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2)) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 128, kernel_size = c(3,3), activation = 'relu') %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2)) %>%

layer_conv_2d(filters = 256, kernel_size = c(3,3), activation = 'relu') %>%

layer_max_pooling_2d(pool_size = c(2, 2)) %>%

layer_dropout(rate = 0.25) %>%

layer_flatten() %>%

layer_dense(units = 128, activation = 'relu') %>%

layer_dropout(rate = 0.5) %>%

layer_dense(units = 30, activation = 'softmax')

```

We used 4 layers of convolutions combined with max pooling layers to extract features from the spectrogram images and 2 dense layers at the top. Our network is comparatevely simple when compared to more advanced archutectures like VGG and DenseNets that perform very well on image recognition tasks.

Now let's compile our model. We will use the categorical crossentropy as the loss function and use the Adadelta optimizer. It's also here that we define that we will look at the accuracy metric during training.

```{r}

model %>% compile(

loss = loss_categorical_crossentropy,

optimizer = optimizer_adadelta(),

metrics = c('accuracy')

)

```

## Model fitting

Now, we will fit our model. In Keras we can use TensorFlow Datasets as inputs to the the `fit_generator` function and we will will do it here.

```{r}

model %>% fit_generator(

generator = ds_train,

steps_per_epoch = 0.7*nrow(df)/32,

epochs = 10,

validation_data = ds_test,

validation_steps = 0.3*nrow(df)/32

)

```

```

Epoch 1/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 87s 62ms/step - loss: 2.0225 - acc: 0.4184 - val_loss: 0.7855 - val_acc: 0.7907

Epoch 2/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 75s 53ms/step - loss: 0.8781 - acc: 0.7432 - val_loss: 0.4522 - val_acc: 0.8704

Epoch 3/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 75s 53ms/step - loss: 0.6196 - acc: 0.8190 - val_loss: 0.3513 - val_acc: 0.9006

Epoch 4/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 75s 53ms/step - loss: 0.4958 - acc: 0.8543 - val_loss: 0.3130 - val_acc: 0.9117

Epoch 5/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 75s 53ms/step - loss: 0.4282 - acc: 0.8754 - val_loss: 0.2866 - val_acc: 0.9213

Epoch 6/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 76s 53ms/step - loss: 0.3852 - acc: 0.8885 - val_loss: 0.2732 - val_acc: 0.9252

Epoch 7/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 75s 53ms/step - loss: 0.3566 - acc: 0.8991 - val_loss: 0.2700 - val_acc: 0.9269

Epoch 8/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 76s 54ms/step - loss: 0.3364 - acc: 0.9045 - val_loss: 0.2573 - val_acc: 0.9284

Epoch 9/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 76s 53ms/step - loss: 0.3220 - acc: 0.9087 - val_loss: 0.2537 - val_acc: 0.9323

Epoch 10/10

1415/1415 [==============================] - 76s 54ms/step - loss: 0.2997 - acc: 0.9150 - val_loss: 0.2582 - val_acc: 0.9323

```

The model accuracy was 93.23%. Let's learn how to make predictions and take a look at the confusion matrix.

## Making predictions

We can use the`predict_generator` function to make predictions to a new dataset. Let's make predictions for our test dataset.

The `predict_generator` function needs a step argument which is the number of times the generator will be called.

We can calculate the number of steps by knowing the batch size, and the size of the test dataset.

```{r}

df_test <- df[-id_train,]

n_steps <- nrow(df_test)/32 + 1

```

We can then use the `predict_generator` function:

```{r}

predictions <- predict_generator(

model,

ds_test,

steps = n_steps

)

str(predictions)

```

```

num [1:19424, 1:30] 1.22e-13 7.30e-19 5.29e-10 6.66e-22 1.12e-17 ...

```

This will output a matrix with 30 columns - one for each word and n_steps*batch_size number of rows. Note that it starts repeating the dataset at the end to create a full batch.

We can compute the predicted class by taking the column with the the greater probability, for example.

```{r}

classes <- apply(predictions, 1, which.max) - 1

```

A nice visualization of the confusion matrix is to create an alluvial diagram:

```{r}

library(dplyr)

library(alluvial)

x <- df_test %>%

mutate(pred_class_id = head(classes, nrow(df_test))) %>%

left_join(

df_test %>% distinct(class_id, class) %>% rename(pred_class = class),

by = c("pred_class_id" = "class_id")

) %>%

mutate(correct = pred_class == class) %>%

count(pred_class, class, correct)

alluvial(

x %>% select(class, pred_class),

freq = x$n,

col = ifelse(x$correct, "lightblue", "red"),

border = ifelse(x$correct, "lightblue", "red"),

alpha = 0.6,

hide = x$n < 20

)

```

We can see from the diagram that the most relevant mistake our model makes is to classify "tree" as "three". There are other common errors like classifying "go" and "no", "up" as "off". With 93% of accuracy and considering the errors we can say that this model is pretty reasonable.

The saved model ocuppies 25Mb in disk, which is reasonable for a desktop but may not be for using in small devices. We could train a smaller model, with less layers, and see how much the performance decreases.

In speech recognition tasks it's also common to do some kind of data augmentation by mixing a background noise to the spoken audio making it more usefull for real applications where it's common to have other irrelevant sounds happening in the environment.