David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens is part of HackerNoon’s Book Blog Post series. You can jump to any chapter in this book here: [LINK TO TABLE OF LINK]. PREFACE TO THE CHARLES DICKENS EDITION

David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens is part of HackerNoon’s Book Blog Post series. You can jump to any chapter in this book here: [LINK TO TABLE OF LINK]. PREFACE TO THE CHARLES DICKENS EDITION

For years and years, Mr. Barkis had carried this box, on all his journeys, every day.

For years and years, Mr. Barkis had carried this box, on all his journeys, every day.

She did not once show me any change in herself. What she always had been to me, she still was; wholly unaltered.

She did not once show me any change in herself. What she always had been to me, she still was; wholly unaltered.

The general air of the place reminded me forcibly of the days when I lived with Mr. and Mrs. Micawber.

The general air of the place reminded me forcibly of the days when I lived with Mr. and Mrs. Micawber.

I try to stay my tears, and to reply, ‘Oh, Dora, love, as fit as I to be a husband!’

I try to stay my tears, and to reply, ‘Oh, Dora, love, as fit as I to be a husband!’

From the first moment of her dark eyes resting on me, I saw she knew I was the bearer of evil tidings.

From the first moment of her dark eyes resting on me, I saw she knew I was the bearer of evil tidings.

But who is this that breaks upon me? This is Miss Shepherd, whom I love.

But who is this that breaks upon me? This is Miss Shepherd, whom I love.

Once again, let me pause upon a memorable period of my life. Let me stand aside, to see the phantoms of those days go by me, accompanying the shadow of myself.

Once again, let me pause upon a memorable period of my life. Let me stand aside, to see the phantoms of those days go by me, accompanying the shadow of myself.

In due time, Mr. Micawber’s petition was ripe for hearing; and that gentleman was ordered to be discharged under the Act, to my great joy.

In due time, Mr. Micawber’s petition was ripe for hearing; and that gentleman was ordered to be discharged under the Act, to my great joy.

‘Why, bless my life and soul!’ said Mr. Omer, ‘how do you find yourself? Take a seat.—-Smoke not disagreeable, I hope?’

‘Why, bless my life and soul!’ said Mr. Omer, ‘how do you find yourself? Take a seat.—-Smoke not disagreeable, I hope?’

One day I was informed by Mr. Mell that Mr. Creakle would be home that evening.

One day I was informed by Mr. Mell that Mr. Creakle would be home that evening.

‘Good-bye for ever. Now, my dear, my friend, good-bye for ever in this world.

‘Good-bye for ever. Now, my dear, my friend, good-bye for ever in this world.

My new life had lasted for more than a week, and I was stronger than ever in those tremendous practical resolutions that I felt the crisis required.

My new life had lasted for more than a week, and I was stronger than ever in those tremendous practical resolutions that I felt the crisis required.

And now my written story ends. I look back, once more—for the last time—before I close these leaves.

And now my written story ends. I look back, once more—for the last time—before I close these leaves.

A fearful cry followed the word. I paused a moment, and looking in, saw him supporting her insensible figure in his arms.

A fearful cry followed the word. I paused a moment, and looking in, saw him supporting her insensible figure in his arms.

The wind had gone down with the light, and so the snow had come on. It was a heavy, settled fall, I recollect, in great flakes; and it lay thick.

The wind had gone down with the light, and so the snow had come on. It was a heavy, settled fall, I recollect, in great flakes; and it lay thick.

A glimpse of the river through a dull gateway, where some waggons were housed for the night, seemed to arrest my feet.

A glimpse of the river through a dull gateway, where some waggons were housed for the night, seemed to arrest my feet.

I left all who were dear to me, and went away; and believed that I had borne it, and it was past.

I left all who were dear to me, and went away; and believed that I had borne it, and it was past.

It was fine in the morning, particularly in the fine mornings. It looked a very fresh, free life, by daylight: still fresher, and more free, by sunlight.

It was fine in the morning, particularly in the fine mornings. It looked a very fresh, free life, by daylight: still fresher, and more free, by sunlight.

It is not my purpose, in this record, though in all other essentials it is my written memory, to pursue the history of my own fictions.

It is not my purpose, in this record, though in all other essentials it is my written memory, to pursue the history of my own fictions.

David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens is part of the HackerNoon Books series. Read this book online for free on HackerNoon!

David Copperfield, by Charles Dickens is part of the HackerNoon Books series. Read this book online for free on HackerNoon!

I mentioned to Mr. Spenlow in the morning, that I wanted leave of absence for a short time

I mentioned to Mr. Spenlow in the morning, that I wanted leave of absence for a short time

‘The message was right enough, perhaps,’ said Mr. Barkis; ‘but it come to an end there.’

‘The message was right enough, perhaps,’ said Mr. Barkis; ‘but it come to an end there.’

As if, in love, joy, sorrow, hope, or disappointment; in all emotions; my heart turned naturally there, and found its refuge and best friend.

As if, in love, joy, sorrow, hope, or disappointment; in all emotions; my heart turned naturally there, and found its refuge and best friend.

She was exactly the same as ever, and the same immortal butterflies hovered over her cap.

She was exactly the same as ever, and the same immortal butterflies hovered over her cap.

Her idea was my refuge in disappointment and distress, and made some amends to me, even for the loss of my friend.

Her idea was my refuge in disappointment and distress, and made some amends to me, even for the loss of my friend.

‘Now’s the day, and now’s the hour,

See the front of battle lower,

See approach proud EDWARD’S power—

Chains and slavery!

‘Now’s the day, and now’s the hour,

See the front of battle lower,

See approach proud EDWARD’S power—

Chains and slavery!

I forgot them; while I was picking them up, I dropped the other fragments of the system; in short, it was almost heart-breaking.

I forgot them; while I was picking them up, I dropped the other fragments of the system; in short, it was almost heart-breaking.

He drew her to him, whispered in her ear, and kissed her.

He drew her to him, whispered in her ear, and kissed her.

I never saw a man so hot in my life. I tried to calm him, that we might come to something rational; but he got hotter and hotter, and wouldn’t hear a word.

I never saw a man so hot in my life. I tried to calm him, that we might come to something rational; but he got hotter and hotter, and wouldn’t hear a word.

It was no matter of wonder to me to find Mrs. Steerforth devoted to her son.

It was no matter of wonder to me to find Mrs. Steerforth devoted to her son.

I PASS over all that happened at school, until the anniversary of my birthday came round in March.

I PASS over all that happened at school, until the anniversary of my birthday came round in March.

‘My dear Copperfield, a man who labours under the pressure of pecuniary embarrassments, is, with the generality of people, at a disadvantage.

‘My dear Copperfield, a man who labours under the pressure of pecuniary embarrassments, is, with the generality of people, at a disadvantage.

If it had been Aladdin’s palace, roc’s egg and all, I suppose I could not have been more charmed with the romantic idea of living in it.

If it had been Aladdin’s palace, roc’s egg and all, I suppose I could not have been more charmed with the romantic idea of living in it.

I could not get over this farewell glimpse of them for a long time.

I could not get over this farewell glimpse of them for a long time.

I have often remarked—I suppose everybody has—that one’s going away from a familiar place, would seem to be the signal for change in it.

I have often remarked—I suppose everybody has—that one’s going away from a familiar place, would seem to be the signal for change in it.

There comes out of the cloud, our house—not new to me, but quite familiar, in its earliest remembrance.

There comes out of the cloud, our house—not new to me, but quite familiar, in its earliest remembrance.

‘You will find her,’ pursued my aunt, ‘as good, as beautiful, as earnest, as disinterested, as she has always been.

‘You will find her,’ pursued my aunt, ‘as good, as beautiful, as earnest, as disinterested, as she has always been.

Not that I mean to say these were special marks of distinction, which only I received.

Not that I mean to say these were special marks of distinction, which only I received.

This sentiment gave unbounded satisfaction—greater satisfaction, I think, than anything that had passed yet.

This sentiment gave unbounded satisfaction—greater satisfaction, I think, than anything that had passed yet.

It was, to conceal what had occurred, from those who were going away; and to dismiss them on their voyage in happy ignorance. In this, no time was to be lost.

It was, to conceal what had occurred, from those who were going away; and to dismiss them on their voyage in happy ignorance. In this, no time was to be lost.

I know enough of the world now, to have almost lost the capacity of being much surprised by anything

I know enough of the world now, to have almost lost the capacity of being much surprised by anything

I had advanced in fame and fortune, my domestic joy was perfect, I had been married ten happy years.

I had advanced in fame and fortune, my domestic joy was perfect, I had been married ten happy years.

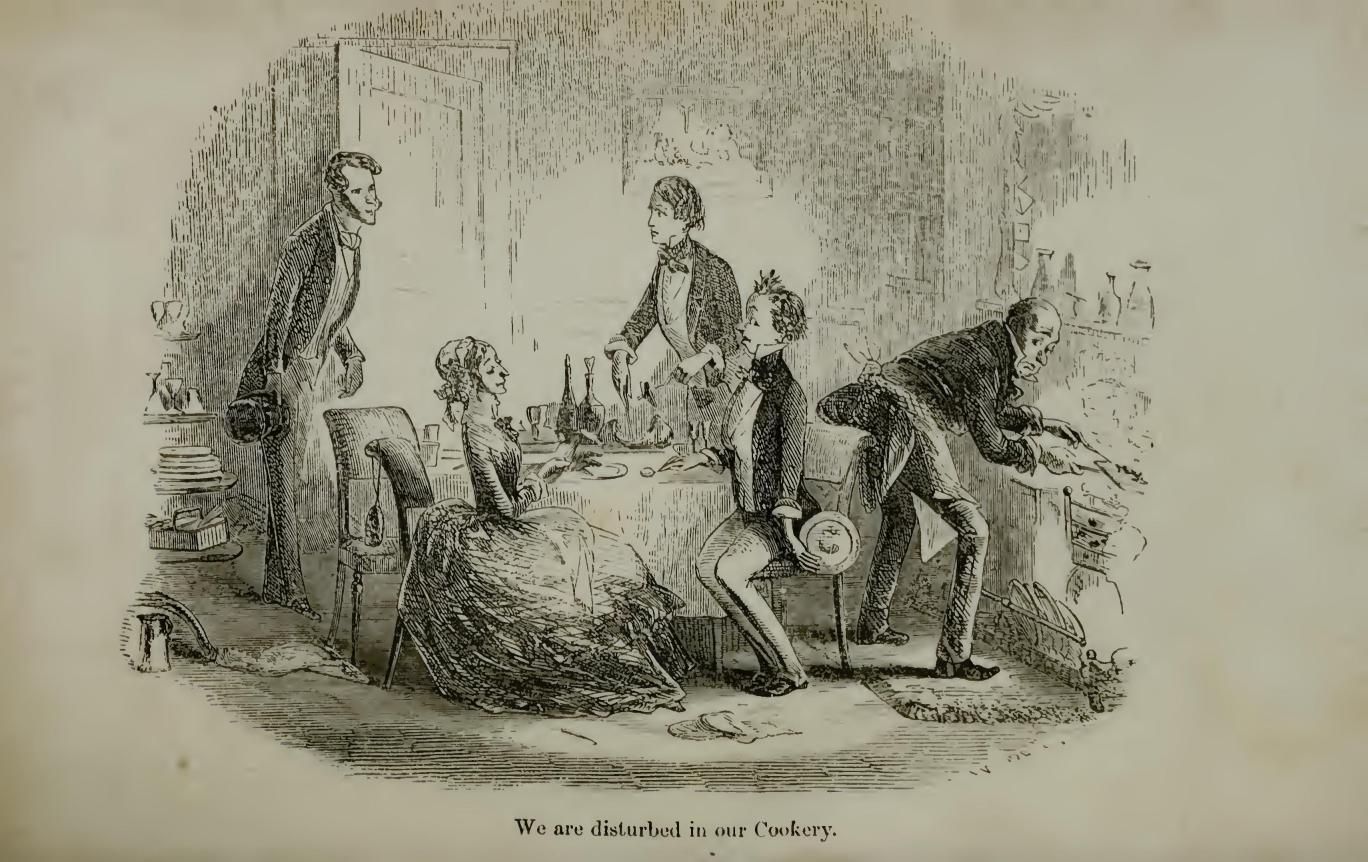

Until the day arrived on which I was to entertain my newly-found old friends, I lived principally on Dora and coffee.

Until the day arrived on which I was to entertain my newly-found old friends, I lived principally on Dora and coffee.

Mr. Dick and I soon became the best of friends, and very often, when his day’s work was done, went out together to fly the great kite.

Mr. Dick and I soon became the best of friends, and very often, when his day’s work was done, went out together to fly the great kite.

What is natural in me, is natural in many other men, I infer, and so I am not afraid to write that I never had loved Steerforth

What is natural in me, is natural in many other men, I infer, and so I am not afraid to write that I never had loved Steerforth

His honest face, as he looked at me with a serio-comic shake of his head, impresses me more in the remembrance than it did in the reality.

His honest face, as he looked at me with a serio-comic shake of his head, impresses me more in the remembrance than it did in the reality.

I am doubtful whether I was at heart glad or sorry, when my school-days drew to an end, and the time came for my leaving Doctor Strong’s.

I am doubtful whether I was at heart glad or sorry, when my school-days drew to an end, and the time came for my leaving Doctor Strong’s.

When I awoke in the morning I thought very much of little Em’ly, and her emotion last night, after Martha had left.

When I awoke in the morning I thought very much of little Em’ly, and her emotion last night, after Martha had left.

We might have gone about half a mile, and my pocket-handkerchief was quite wet through, when the carrier stopped short.

We might have gone about half a mile, and my pocket-handkerchief was quite wet through, when the carrier stopped short.

—all the romance of our engagement put away upon a shelf, to rust—no one to please but one another—one another to please, for life.

—all the romance of our engagement put away upon a shelf, to rust—no one to please but one another—one another to please, for life.

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

Whether I shall turn out to be the hero of my own life, or whether that station will be held by anybody else, these pages must show.

Such a self-contained man I never saw.

Such a self-contained man I never saw.

The vaunting cruelty with which she met my glance, I never saw expressed in any other face that ever I have seen.

The vaunting cruelty with which she met my glance, I never saw expressed in any other face that ever I have seen.

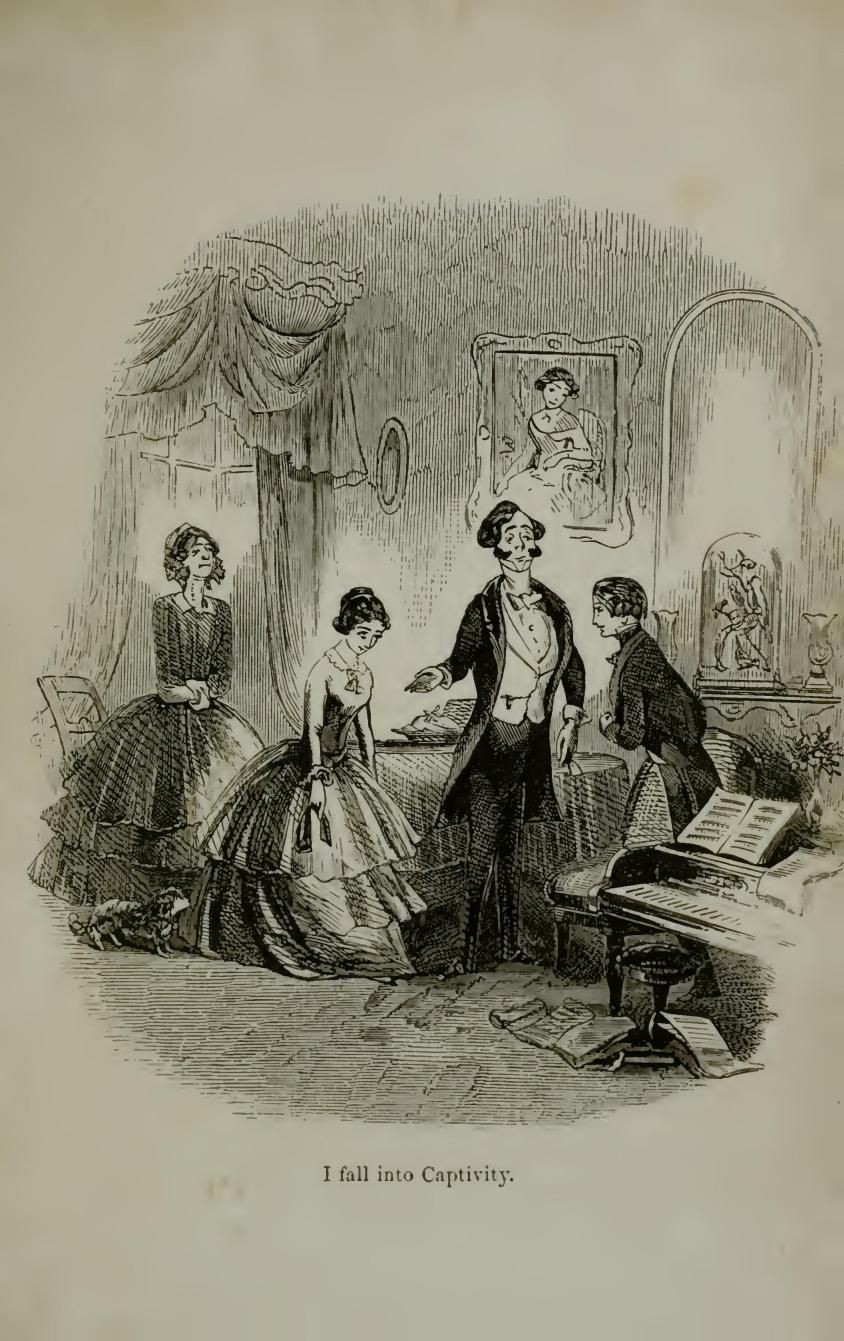

With the new life, came new purpose, new intention. Great was the labour; priceless the reward. Dora was the reward, and Dora must be won.

With the new life, came new purpose, new intention. Great was the labour; priceless the reward. Dora was the reward, and Dora must be won.

I could scarcely lay claim to the name: I was so disturbed by the conviction that the letter came from Agnes.

I could scarcely lay claim to the name: I was so disturbed by the conviction that the letter came from Agnes.

‘My dear,’ said my aunt, after taking a spoonful of it; ‘it’s a great deal better than wine. Not half so bilious.’

‘My dear,’ said my aunt, after taking a spoonful of it; ‘it’s a great deal better than wine. Not half so bilious.’

And Mrs. Gummidge took his hand, and kissed it with a homely pathos and affection, in a homely rapture of devotion and gratitude, that he well deserved.

And Mrs. Gummidge took his hand, and kissed it with a homely pathos and affection, in a homely rapture of devotion and gratitude, that he well deserved.

My spirits sank under these words, and I became very downcast and heavy of heart.

My spirits sank under these words, and I became very downcast and heavy of heart.

‘I suppose history never lies, does it?’ said Mr. Dick, with a gleam of hope.

‘I suppose history never lies, does it?’ said Mr. Dick, with a gleam of hope.

Next morning, after breakfast, I entered on school life again. I went, accompanied by Mr. Wickfield, to the scene of my future studies

Next morning, after breakfast, I entered on school life again. I went, accompanied by Mr. Wickfield, to the scene of my future studies

A plan had occurred to me for passing the night, which I was going to carry into execution.

A plan had occurred to me for passing the night, which I was going to carry into execution.

I saw, in my aunt’s face, that she began to give way now, and Dora brightened again, as she saw it too.

I saw, in my aunt’s face, that she began to give way now, and Dora brightened again, as she saw it too.

Steerforth and I stayed for more than a fortnight in that part of the country.

Steerforth and I stayed for more than a fortnight in that part of the country.

My meaning simply is, that whatever I have tried to do in life, I have tried with all my heart to do well;

My meaning simply is, that whatever I have tried to do in life, I have tried with all my heart to do well;