NOTE: This is currently a work-in-progress - it just includes the Operational excellence and Security pillars so far

The AWS Well Architected Framework helps you understand the pros and cons of decisions you make while building systems on AWS and helps you to learn architectural best practices for designing and operating reliable, secure, efficient, cost-effective, and sustainable systems in the cloud.

Kubernetes, even when run as the Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS) on AWS, is nearly a full cloud in its own right. That is why people can run it on bare-metal within their own data centres - not just in public clouds like AWS. So, running EKS is rather like running a cloud on a cloud - with some integrations between the two. So, running your workloads on top of EKS has major implications for attempting to apply the framework. AWS hasn't (yet?) addressed these implications themselves (outside of the EKS Best Practices Guide) - so this is my attempt to do so.

NOTE: This is my (Jason Umiker's) subjective view of this space. It doesn't come from AWS - though I do hope that they extend Well Architected with an EKS lens themselves someday soon. And I am open to any suggestions via Issues/Pull Requests against this repository you may have.

The AWS Well Architected Framework is made up of six pillars:

- Operational excellence

- Security

- Reliability

- Performance efficiency

- Cost optimization

- Sustainability

And then within each pillar there are variety of best practices that AWS suggests. I have gone through this list to evaluate each of them with a Kubernetes/EKS lens in mind. I'll only comment on those where a workload being on Kubernetes/EKS might change the way you'd think about it vs. a more native AWS approach (so you can assume if it isn't listed here that I consider the traditional AWS WAR guidance sufficient).

This set of best practices is focused on implementing observability in your workload so that you can understand its state and make data-driven decisions based on business requirements.

One area where EKS differs from most of the other AWS services is that there is no observability (metrics, logs or traces) enabled by default. This is because customers have a key decision to make - one that can be strategic for them.

The three possible paths to observability with EKS are:

- Use the traditional AWS native approaches (e.g. CloudWatch, CloudWatch Logs, X-Ray) - This approach is appropriate if all of your workloads are in AWS and so it makes sense to standardize on their native, yet AWS-proprietary, observability services. For metrics and logs AWS calls this approach CloudWatch Container Insights (https://docs.aws.amazon.com/AmazonCloudWatch/latest/monitoring/deploy-container-insights-EKS.html).

- You can use the open-source vendor-agnostic tooling in this space (e.g. Prometheus, Elastic/OpenSearch, Jaeger) - This approach is approach is appropriate if you are trying to use consistent tooling both in and out of AWS. And Prometheus and Jaeger are not just open-source, but also governed by the same vendor-neutral organization that governs Kubernetes - the Cloud Native Computing Foundation (CNCF). And, thanks in large part to AWS, ElasticSearch has been forked to be truly open and free in OpenSearch.

- AWS actually runs managed services for Prometheus as well as OpenSearch - giving you the best of both worlds (a managed service but based on a vendor-agnostic opensource tool that you could run yourself anywhere)

- And at re:Invent this year they announced a tighter opt-in integration with their Managed Service for Prometheus with EKS

- AWS actually runs managed services for Prometheus as well as OpenSearch - giving you the best of both worlds (a managed service but based on a vendor-agnostic opensource tool that you could run yourself anywhere)

- You can use non-AWS commercial SaaS services in this observability space (Sysdig Monitor, Datadog, AppDynamics, NewRelic, Elastic, Splunk, SumoLogic etc.) - This approach can work for both hybrid and multi-cloud environments - but at a cost of both money and a degree of lock-in to the SaaS vendor.

Also, one of the key considerations for which path to choose is the extent to which you'll need to change your code. As, for metrics and traces, you often need to instrument your code with an SDK like CloudWatch and X-Ray or Prometheus and Jaegar. So, changing tools usually means changes to your code (even though those changes are usually fairly minor/boilerplate). Many of the commercial SaaS offerings also have proprietary agents - so changing tools means changing out all the agents too. This cost-to-change is now often being mitigated, though, with OpenTelemetry. OpenTelemetry is a CNCF project focused on being one agent and SDK that can serve all your metrics, logging and tracing needs while being plugable to all the common backend tools/services. And AWS supports this approach with their own AWS Distro for OpenTelemetry.

Finally, this observability data is often needed by automation such as the Kubernetes Horizontal Pod Autoscaler (HPA) (to know when to scale your workload in/out) or by tools like Argo Rollouts or Flagger (to know when a deployment has issues and should be automatically rolled back). So, understanding what tools you plan on using and what observability backends those tools will need as a source is a consideration here as well.

This set of best practices is focused on adopting approaches that improve the flow of changes into production, that activate refactoring, fast feedback on quality, and bug fixing. These accelerate beneficial changes entering production, limit issues deployed, and achieve rapid identification and remediation of issues introduced through deployment activities.

What both Kubernetes/EKS and an AWS-native approach have in common here are that you should:

- Manage your infrastructure via code (IaC)

- Version control both your code, as well as the associated IaC, in a source repository like git

- Check whether known vulnerabilities (CVEs) in your code, the opensource packages you use from npm/pip/maven/nuget etc. or the OS (Ubuntu, Debian, Alpine, etc.) and/or application runtime (Node, Python, Java, .NET etc.) base layers of your container images

- Have automated pipelines to build as well as deploy your application - ideally along with any cloud infrastructure-as-code it depends on as well

- Test that your application and associated IaC work by actually deploying them 'for real' in a non-production but production-like environment (rather than just with static tests and mocks) before going to production

- And if you build production end-to-end with IaC it is much easier to make a cloned "production-like" environment

But there are some differences in both tooling and flow when it comes to having a "best practice" Kubernetes deployment flow vs. native AWS.

Firstly, Kubernetes/EKS is different in that it is declarative rather than imperative like AWS. The imperative IaC approach tells the system to create or update specific resource(s) right now, while the declarative approach tells the system what your desired end-state is - and it figures out how to make it happen as well as keep it that way. With the imperative approach, once that resource exists you can 'drift' away from it if you change the resource outside the IaC in the console or API. Whereas Kubernetes has a control loop where, if you change resources so they no longer match what you had declared, then it will immediately try to put them back - continually reverting any drift that happens as soon as it happens.

Also, in Kubernetes everything is a declarative YAML IaC file. Even if you make what seems like an imperative command to create/update something with kubectl, it is just generating the YAML IaC file and submitting it for you. Putting these two concepts together (everything being declarative IaC), The analogy with native AWS would be to imagine if you could only manage AWS with CloudFormation - and anything you did with the AWS Console or CLI generated the CloudFormation templates and applied them into Stacks for you. And that if you tried to introduce any drift vs. what was in the deployed Stacks then AWS would immediately revert back to what you declared in your IaC.

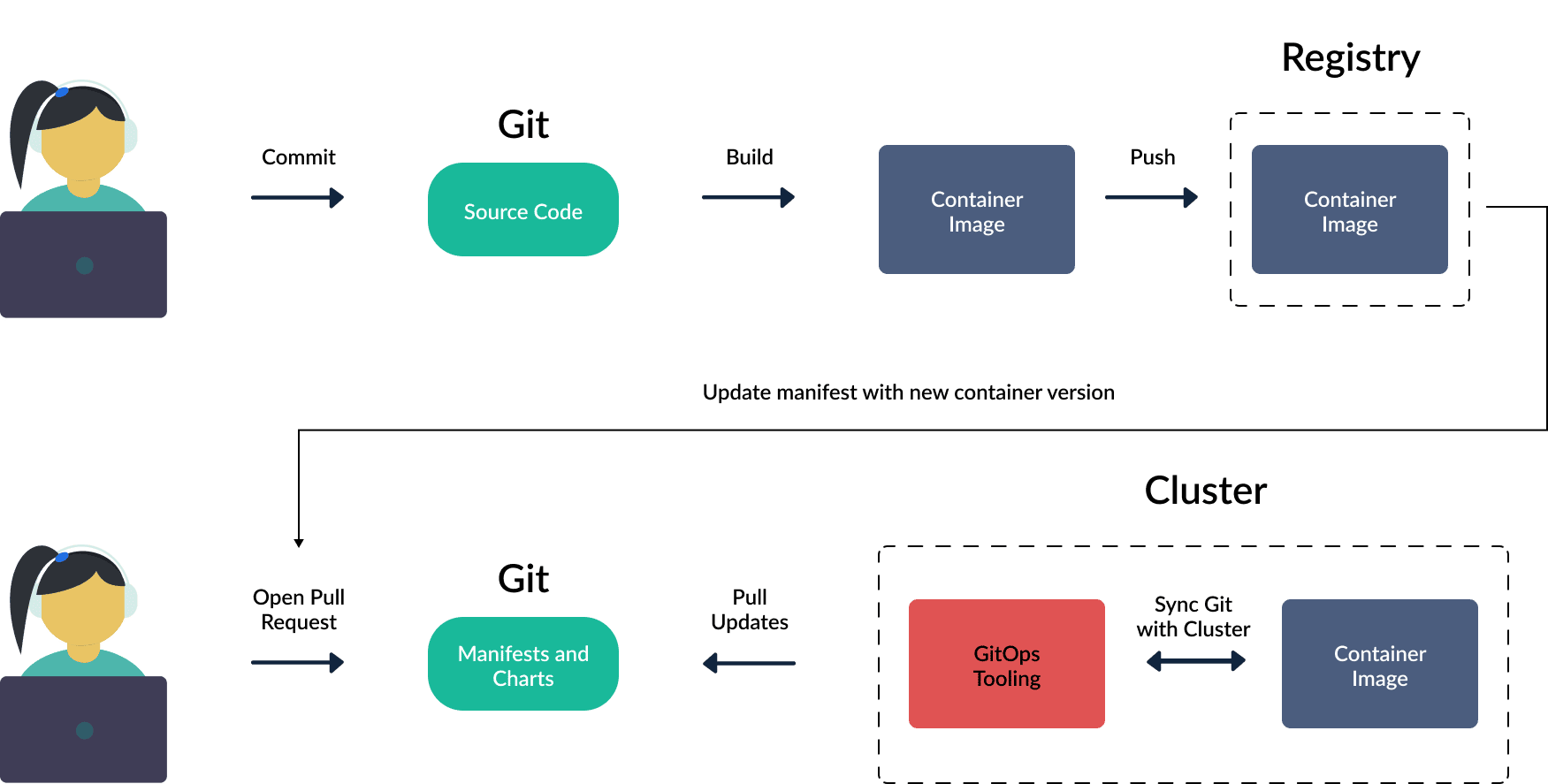

This fundamental difference allows for some significant changes in both tooling as well as what are the best practices for the platform. The 'best practice' flow in Kubernetes with this all in mind is called GitOps. And here is what that flow looks like:

The two common Kubernetes GitOps tools are ArgoCD and Flux. What they have in common is:

- They run within your cluster(s) and pull in newly merged changes from git repos/branches (rather than have a stage of your pipeline run a CLI command to push them to the cluster/cloud)

- They, therefore, move the security challenge from controlling access to the cluster (e.g. authx of

kubectlto make the required changes) to controlling who can merge to the git repo - because whatever gets merged to particular repos/branches will be deployed immediately by the GitOps operator- This often takes the form of requiring changes via Pull Request (PR) with a mandatory pre-merge testing and approval flow

- They, therefore, move the security challenge from controlling access to the cluster (e.g. authx of

One of the key challenges when it comes to running EKS is that you often need to mix these tools and approaches - use CloudFormation or Terraform to create the VPC, create the EKS cluster, create the RDS Databases, etc. - and then you use the K8s YAML with ArgoCD or Flux to manage the containerized applications on Kubernetes. Some people don't want to use two different tools/flows - and that is why AWS developed the AWS Controllers for Kubernetes so that you can mange AWS from within EKS via declarative YAML like you do with your apps. There is also the CNCF project Crossplane that takes a similar approach of extending Kubernetes to manage the underlying public cloud - but it can do it not just for AWS but for Azure and GCP as well!

We'll cover this in more detail under the security pillar, but it is both advisable - as well as quite easy - to scan your container images for known vulnerabilities, or CVEs, in your build pipelines before they get pushed to your registry or deployed. This can be done with AWS Inspector as well as a number of 3rd party tools such as Trivy, Docker Scout (built into the Docker CLI), Synk Container and Sysdig.

This set of best practices is focused on adopting approaches that provide fast feedback on quality and achieve rapid recovery from changes that do not have desired outcomes. Using these practices mitigates the impact of issues introduced through the deployment of changes.

Things that both an EKS/Kubernetes and AWS-native approach have in common here are that:

- You should plan for unsuccessful deployments

- Deployments should be automated

- There should be automated testing to determine if deployments are successful

- Deployments should be via release models/flows such as:

- Blue/green - where you run the new and old version at the same time and only flip (all) the traffic once the new version has tested successfully

- Canary or Progressive Delivery - where you send a small percentage of your traffic and/or customers to the new version and then gradually increase it in an automated and controlled way

- This allows you to only impact a subset of your users with any problems introduced by your changes rather than all of them

- It also doesn't require running as much infrastructure (as much as double) - as the old version is usually automatically scaled in after the new version is scaled out as the traffic is gradually shifted across

For Kubernetes, there are two tools dedicated to helping you achieve these goals that align with which of the GitOps operators that you choose - Argo Rollouts when using ArgoCD and Flagger when using Flux. And, should you embrace Kubernetes GitOps with those tools (like we talked about for OPS 5), then you should also keep going and embrace their associated advanced deployment tools to fully automate the process and help mitigate deployment risks.

These tools will do things like:

- Facilitate automated blue/green or canary deployments

- Monitor and validate service level objectives (SLOs) like availability, error rate percentage, average response time and any other objective based on app specific metrics around the deployment - and automatically roll back deployments that fail these metrics (with minimal impact to end-users)

- This requires you to have configured an appropriate observability tool as described in OPS 4 from which Rollouts/Flagger will get these metrics

Well architected is usually focused on workloads rather than on the cluster(s) that they run on - but Kubernetes/EKS has a new version every quarter and the clusters also require regular upgrades as part of their ongoing operation as well. And those cluster upgrades can have impacts on the performance and availability of the apps running on them.

There are quite a few considerations here and AWS has documented it all quite well in their EKS Best Practices Guide - so I'll refer you to the relevant section of that for more details.

This set of best practices is focused on your multi-account strategy in AWS as well as having automated security testing/validation in place within the pipelines that deploy your code and IaC. It also speaks to having an appropriate threat model for each of your workloads.

In AWS, splitting workloads between different accounts has two key benefits:

- The AWS IAM is much harder to accidentally 'mess up' where admins or workloads get access to things that they shouldn't

- Because, while you technically can achieve some of this with fine-grained/least-privilege AWS IAM within an account, it is a much 'harder' boundary to just use separate AWS accounts

- Separate AWS accounts is especially suggested between development and production environments for this reason - as you often want developers to have more access to make changes and see the databases etc. while experimenting and 'moving fast' in the development environment than in production

- Because, while you technically can achieve some of this with fine-grained/least-privilege AWS IAM within an account, it is a much 'harder' boundary to just use separate AWS accounts

- You get your bills split by AWS account so it is easier to attribute cost to different environments/teams/workloads if they map to AWS accounts

- Because, while you technically can achieve some of this with a fine-grained tagging strategy aligned with your billing within a single account, you get it 'for free' if things are in different AWS accounts

Since Kubernetes is nearly a private cloud running on your public cloud, you can make the same two arguments for having separate EKS clusters:

- It is much harder to accidentally 'mess up' where admins or workloads get access to things they shouldn't in the Kubernetes API

- Because, while you technically can achieve some of this with fine-grained/least privilege Kubernetes RBAC and Namespaces within a cluster, it is a much 'harder' boundary to just use separate EKS clusters

- With EKS, it also isn't just the API's RBAC/boundaries that matter - the workloads share the same underlying Nodes and Linux Kernel(s) too - and so noisy neighbors and container escapes are a concern

- And, while it is possible to configure your cluster's and workloads' posture to mostly prevent those (don't allow insecure Pod parameters, ensure every workload has cpu/memory requests and limits defined, etc.), it is a much 'harder' boundary between workloads to just have them on separate clusters - which also ensures they are deployed onto separate Nodes as well (as clusters can't share underlying compute Nodes)

- Your cloud bills will be for the Nodes - not the containerized workloads running on them - so separate clusters will also make it easier to attribute cost to different teams/workloads (especially if you also put them in separate AWS accounts)

This is all to say that when EKS is involved you now have to consider when things should run on the same cluster vs. when they shouldn't - and in addition to what AWS account they should run in. And since one EKS cluster can't run in multiple AWS accounts - the AWS account splitting decision also impacts the EKS one as well.

AWS goes into more detail in how to think about this in their Tenant Isolation section of the EKS Best Practices Guide. It coins the terms 'soft multi-tenancy' for sharing clusters and 'hard multi-tenancy' for when you split things into separate clusters.

The best practices in the framework for this question are often described as DevSecOps (i.e. including Security in the middle of your DevOps) or "shifting security left" earlier into the process - into the pipelines which build and deploy your apps. They ask you to:

- Establish secure baselines and templates that are tested

- Use automation to test and validate security controls continuously

- "For example, scan items such as machine images and IaC templates for security vulnerabilities, irregularities and drift from an established baseline at each stage"

- Design CI/CD pipelines that test for security issues at each stage

- Track changes to your workload to help with compliance auditing, change management and investigations

These would all apply if deploying to EKS too - but with these sometime subtle nuances:

- Establish secure baselines and templates that are tested

- Some sensible security baselines for your Kubernetes IaC manifests are defined by the Kubernetes project as the Pod Security Standards. These control the parameters you can put in your PodSpec that would allow for things like privilege escalation and/or container escapes.

- It can be difficult to meet the top restricted standard, though, so having templates ready to go for your colleagues that meet that standard can help smooth adoption

- This is as opposed to the baseline standard which, pragmatically, still blocks most of the insecure PodSpec parameters that can lead to privilege escalation and/or container escapes while usually not requiring changes to most Kubernetes manifests/IaC or apps (like restricted)

- It can be helpful to build 'trusted' container base images/layers for everyone to use

- As this means that you only need to patch vulnerabilities once, and in one place, and all of your subsequent container builds by all of your teams will pick up that work

- Some sensible security baselines for your Kubernetes IaC manifests are defined by the Kubernetes project as the Pod Security Standards. These control the parameters you can put in your PodSpec that would allow for things like privilege escalation and/or container escapes.

- Use automation to test and validate security controls continuously

- When it comes to the IaC, Kubernetes has a built-in Admission Controller that will look at the IaC being deployed and refuse to deploy any whose parameters don't meet your requirements. So, rather than the needing to configure pipelines to provide our security outside of the cloud/cluster, you can actually ask the Kubernetes to enforce it at runtime for you inside the API.

- If you put appropriate labels on your Namespaces then the built-in Pod Security Admission Controller will enforce whatever your nominated Pod Security Standard is for you on anything being deployed to the cluster.

- And, for more elaborate/extensive controls, Open Policy Agent's Gatekeeper or Kyverno can control the admission of nearly anything within Kubernetes IaC

- The one thing that an Admission Controller doesn't give you is historical reporting on what specifically has passed or failed over time that you can show to an auditor or executive - especially one that is mapped against the various compliance standards (CIS, NIST, SOC2, PCI DSS, etc.) relevant to your business

- AWS doesn't have this capability in Config/Security Hub today but there are a number of commercial Cloud Security Posture Management (CPSM) vendors that help here (Sysdig, Aqua, etc.). And many call their specific posture support of Kubernetes KSPM - highlighting that Kubernetes has unique requirements that many CSPM offerings don't cater for.

- When it comes to the IaC, Kubernetes has a built-in Admission Controller that will look at the IaC being deployed and refuse to deploy any whose parameters don't meet your requirements. So, rather than the needing to configure pipelines to provide our security outside of the cloud/cluster, you can actually ask the Kubernetes to enforce it at runtime for you inside the API.

- Design CI/CD pipelines that test for security issues at each stage

- Putting container image vulnerability scans in your CI pipelines - in between when the container image is built and when it is pushed to the registry - is important to keep known vulnerabilities out of your environment as well as to give instant feedback that teams can iterate against

- And AWS just added the ability to do this in your pipelines outside of ECR with Inspector at re:Invent this year

- In addition to AWS Inspector, a number of 3rd party tools such as Trivy, Docker Scout (built into the Docker CLI), Synk Container and Sysdig can help you here.

- Even if you leverage an Admission Controller, it is often a better user experience to also have tests in your pipelines to let a developer know that, if they try to deploy the manifests, it will fail - rather than their learning that at deployment time

- Note that, if you are using a GitOps operator (ArgoCD or Flux), posture tests against the IaC/manifests should be done against any Pull Requests before they are merged to the branch that represents that environment (and therefore going to be deployed)

- Putting container image vulnerability scans in your CI pipelines - in between when the container image is built and when it is pushed to the registry - is important to keep known vulnerabilities out of your environment as well as to give instant feedback that teams can iterate against

- Track changes to your workload to help with compliance auditing, change management and investigations

- If you follow the Kubernetes GitOps processes/flow then every change has to pass through git as a separate commit - and so you are guaranteed to have a full audit trail

In many Kubernetes customers, these templates and guardrails (as well as the EKS clusters and VPCs etc.) are often built and maintained by the platform team. Platform engineering is a practice built up from DevOps principles that seeks to improve each development team’s security, compliance, costs, and time-to-business value through improved developer experiences and self-service within a secure, governed framework. It's both product-based mindset shift and a set of tools and systems to support it.

This set of best practices is focused on verifying the right identities have access to the right resources under the right conditions.

Kubernetes has its own Authentication and Authorization - but in the case of AWS EKS authentication is (mostly) integrated back into AWS IAM.

One of the ways that AWS has made EKS an AWS service is by integrating it with AWS IAM. By default, any access to the EKS API is done via AWS IAM - but it is possible to optionally switch that to an OpenID Connect (OIDC) identity provider.

You just need to run the AWS CLI command aws eks update-kubeconfig to set it up to leverage your IAM User/Role that you are using with the AWS CLI for kubectl as well.

There is also the ability to create a API token to authenticate as a Kubernetes Service Account with any Kubernetes including EKS. These were intended for use with automation such as CICD pipelines running outside the cluster. Anything running within AWS (EC2, CodeBuild, Lambda, etc.), though, you can easily assign an AWS IAM Role to - and so it is better to have them authenticate via AWS IAM with short-lived credentials handled automatically by AWS instead. And Kubernetes is moving away from long-lived tokens itself in its recent versions - encouraging everyone to call their TokenRequest API (similar to AWS STS) for short-lived tokens as required.

The equivalent to 'assigning an AWS IAM role' to a workload running on EKS is a bit more complicated/indirect than doing it to an EC2 Instance, ECS Task or Lambda Function. With EKS traditionally you have needed to use IAM Roles for Service Accounts (IRSA). This is covered by the documentation above but involves:

- Creating an OIDC Provider for the EKS Cluster

- Setting up an IAM Role for that workload that trusts, not only that OIDC provider, but also the specific Namespaced service account within it

- This IAM Role should, of course, be least-privilege so scoped both by API actions as well as by the resource ID they are acting on etc.

- Adding an annotation to the service account letting EKS know it should get temporary credentials from the Simple Token Service (STS) and mount them in any workloads that use that service account.

NEW: AWS just launched a new alternative method at re:Invent to do this that looks both simpler and less tied to specific EKS clusters (as the OIDC provider for IRSA was tied to a single cluster) called EKS Pod Identity. That should be especially helpful if you need to migrate workloads between EKS clusters. I'll document it further here soon after I have a chance to test it out.

This set of best practices is focused on controlling access to people and machine identities that require access to AWS and your workload. Permissions control who can access what, and under what conditions.

Other than needing to map it through a Service Account with IRSA, the best practices here are the same as any other AWS service in that the Role(s) that you use for workloads to call AWS (for things like S3, DynamoDB, etc.) should have policies that are least privilege both in their API actions as well as specific about what resources they can interact with.

You should not reuse one more general role for several services when you could give a more specifically scoped one to each.

With EKS, you need to control access to the separate Kubernetes API in addition to AWS. And while, by default, authentication with EKS is via AWS IAM, authorization/permissions are controlled within Kubernetes via its Role Based Access Control (RBAC). And, like everything else in Kubernetes, this is done via declarative YAML manifests.

A foundational concept to understand how Kubernetes RBAC works is the Namespace. Namespaces are logical boundaries to separate a cluster to allow for multi-tenancy/sharing of it between multiple services/teams more easily and safely.

People and machines are assigned to either a Role or ClusterRole - a Role lives in and confines the assigned person or machine to a single Namespace while a ClusterRole provides cluster-wide access. And they are assigned to that person or machine via a RoleBinding or ClusterRoleBinding.

So, just assigning users/machines to a Role (rather than a ClusterRole) in different Namespaces goes a long way to isolating their ability to interfere with one another while keeping Kubernetes' RBAC clear and manageable.

This is especially challenging because Kubernetes RBAC is a bit tedious in that it has no denys - only allows. So, if you want have a more granular and least-privilege set of permissions, then it might take many lines of explicit allows to replace a single '*'. There is a built-in ClusterRole that represents full access but explicitly without the '*'s - the admin ClusterRole. You can see the full list by running kubectl get clusterrole admin -o yaml - or you can see this example. Note that it is 315 lines of YAML vs. this very short 9 line block if we used the *'s!

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

name: admin

namespace: namespace

rules:

- apiGroups: ["*"]

resources: ["*"]

verbs: ["*"]

The way that I use the admin ClusterRole is to clone it as a starting point and then remove all the resources and/or verbs that I don't want people to be able to access.

Kubernetes has some best practices for RBAC documented here and, in line with those, things you should consider removing or scoping down are:

- Listing all secrets - not only get (which you'd expect) but also having list and/or watch on

secretswill allow users to reveal the contents of Kubernetes secrets - Workload creation - permission to create a new workload in a Namespace also implicitly grants access to most other resources including Secrets, ConfigMaps and PersistentVolumes that they can mount in their Pods and reveal to the creator (either through an interactive shell into the Pod(s) or by writing code that will expose it via an HTTP endpoint etc.)

- Interactive Shells into running Pods - users with

pod/execcan interactively shell into a Pod where they can see its secrets and reach anything it can via NetworkPolicies and/or SecurityGroups etc. - The escalate and bind and impersonate verbs - these all allow for different kinds of privilege escalation and are generally not required

- Token request - users with create rights on

serviceaccounts/tokencan issue tokens to allow anybody to authenticate as a Kubernetes ServiceAccount - Port Forwarding - users with this can run

kubectl port-forwardto establish a network tunnel into the cluster and reach any service/Pod that is running there

This set of best practices is focused on capturing and analyzing events from logs and metrics to gain visibility. And then taking appropriate action on security events and potential threats to help secure your workload.

The things that differ when it comes to EKS are that:

- EKS has its own control plane and therefore audit trail (independent of AWS CloudTrail)

- This audit trail by default doesn't get retained - you can opt-in to sending it to CloudWatch Logs

- The observability (logs, metrics and traces) of your clusters/workloads are not enabled by default - you have various options to do so as described in OPS 4

- In order to get real/full visibility into what is going on within your workloads at runtime, such as detecting suspicious behaviors which could indicate an active attack, you need to have an agent looking at the syscalls within the Linux kernel on each Node. But it also needs to do so while keeping in mind the container context rather than just the host they happen to be running on at the time - as the containers are 'what matters' in a containerized environment.

- AWS optionally does this via an eBPF probe as part of GuardDuty Runtime Monitoring for EKS

- Falco, also a free open-source CNCF project like Kubernetes, uses an eBPF probe in the kernel as well - but it processes those syscalls locally against an open rules-based engine.

- There are a variety of 3rd party commercial offerings that can help here too - such as Sysdig who are the company that donated Falco to the community.

This set of best practices is focused on ensuring there are multiple layers of defense to help protect from both external and internal network-based threats.

Many of the principles here are the same as with AWS (that you should have granular least-privilege network controls and micro-segmentation) - but with Kubernetes/EKS some of the tooling and flows can be a bit different.

The thing that differs between 'native' AWS and EKS is there are two different options/tools for protecting network resources:

- You can use AWS' native firewall capability - SecurityGroups:

- This is not enabled by default and so you need to enable it by specifying the

ENABLE_POD_ENI=trueoption to the AWS VPC CNI.- This is covered more extensively in the EKS Best Practices Guide.

- There is a list of considerations/provisos in the documentation that you should be familiar with

- This is not enabled by default and so you need to enable it by specifying the

- You can use the Kubernetes native firewall capability - NetworkPolices:

- You can think of NetworkPolicy as a distributed host firewall - the AWS VPC CNI on each host/Node continually reconfigures that Nodes's firewall with the right rules as Pods come and go (and it learns their IPs) based on what the NetworkPolicies have declared should or shouldn't be allowed

- This is not enabled by default with EKS either and so you need to enable it by specifying

ENABLE_NETWORK_POLICY=truein the AWS CNI configuration.- This is covered more extensively in the EKS Best Practices Guide

- There is a great graphical NetworkPolicy editor at https://editor.networkpolicy.io and some great examples at https://github.com/ahmetb/kubernetes-network-policy-recipes

- You can even use both at the same time

- In which case, traffic is only allowed if allowed through them both

- Customers often use NetworkPolicies for firewall rules within the cluster (between things running on it) and Security Group for Pods to control access to other resources in AWS running outside the cluster

These both have advantages and disadvantages:

- SecurityGroups:

- Integrate well with AWS (things like RDS databases' security groups can reference your EKS workload ones for micro-segmentation segmentation etc.) - but that also makes it AWS-specific and proprietary

- Can not be created within Kubernetes using the same IaC/flow - have to already exist and then you reference their AWS IDs in your SecurityGroupPolicies

- You need to allow the Kubelet on all of your Nodes to reach your services in order for the probes to work

- NetworkPolices:

- Integrates well with Kubernetes (e.g. they can have rules based on K8s labels) - but it doesn't integrate well with AWS outside the cluster and might require subnetting to ensure that databases are in their own subnet to use layer-3 CIDR-based rules etc.

- Can be created within Kubernetes with the same YAML IaC as the workloads in teh same deployment flow

- Is not AWS-specific so can be set up the same regardless of whether it is running on-prem or in Azure etc.

Note: There are 3rd party extensions to NetworkPolicy such as CiliumNetworkPolicy that you can use if you implement 3rd party CNI plugins. These will allow things like layer 7 and DNS-based rules. But moving away from both the AWS CNI plugin they support as well as the standard NetworkPolicy of the Kubernetes project is a major decision to be considered.

EKS by default allows access to the Kubernetes Control Plane APIs from the Internet via public endpoints. They give you three choices:

- You can have public access (the default) - this means that both your administrative access as well as your Nodes connects to these public endpoints (via a NAT Gateway etc.)

- You can have private access - this means that the K8s API can only be reached via a private VPC endpoint

- You can have both public and private access - this means things like your Nodes will use the VPC endpoint for their communication but you can still access it via the Internet for administration

In secure environments you usually want to only allow private access and then connect administratively via either a client VPN or via a Jumpbox/Basion within the same VPC.

This set of best practices is focused on establishing multiple layers of defense to help protect compute resources from external and internal threats.

If you can SSH, or start an equivalent interactive session in SSM Session Manager, onto a Node then you can have quite extensive access to the workload/environment - especially if you can also sudo to root. Note that if you are root and run a ps you see all the processes regardless of what Pod they are running on - and you can kill them as well. You can also access any Volumes that they are using (they are all usually mounted onto the Node's filesystem then from there into the Pod). You can also run crictl which is the CLI for containerd (the container runtime used by EKS) and bypass Kubernetes and manage the containers running on that Node directly.

As such, this access should be tightly controlled. SSM Session Manager has advantages over SSH in that it:

- Has centralized access control using IAM

- No inbound ports or need to manage bastion hosts or long-lived SSH keys

- Has centralized logging and auditing of session activity

It is also worth exploring moving your Nodes to Bottlerocket which is a minimal OS where traditional shell access to the Nodes is not even possible.

As discussed in Kubernetes RBAC Best Practices, being able interactively shell into a running container via kubectl exec means that the user has the ability to see all of the secrets of that workload as well as go anywhere on the network that it can via the NetworkPolicy and/or AWS Security Group applied to the workload. Workloads that need access to databases or buckets to function would be good candidates for execing into - as they should have both the credentials and network access to access them if you can shell into them. So this access should be either removed from RBAC or at least tightly audited/controlled.

All of the same is true if somebody were to exploit a Remote Code Execution (RCE) vulnerability where they can break out of the workload via its API endpoint etc. You can detect the behaviors that happen when RCE vulnerabilities get exploited with Falco or the more extensive commercial offering Sysdig and, to a lesser extent, AWS GuardDuty's EKS Runtime Monitoring.

There are certain workloads (Container Network Interface (CNI) add-ons, security tooling, etc.) that needs privileged access to the Node and all the containers running on it. Kubernetes wanted to be able to have these workload be something you can easily schedule via. Kubernetes DaemonSets rather than needing to bake them into your machine image (AMI) etc. So, this means that there are some options you can specify in your manifests asking to the access to escape your container. And there are some components on your EKS cluster that likely use and need those parameters.

The issue is that if you can escape your container, especially if your container is already running as root, you have full access to the Node and everything else running there - even if they are workloads that are running in different Kubernetes Namespaces.

So, controlling container escapes is largely about controlling access to those parameters as discussed in SEC 1 via things like Pod Security Admission and other Admission Controllers like OPA Gatekeeper - ensuring they are only used by workloads that need them.

There is also a risk of a zero-day bug in the Linux kernel or Kubernetes that would allow for a container escape. In that case, being able to detect that it is happening using a tool like Falco would be an important capability. It also feeds into

This set of best practices is focused on protecting your data at rest by implementing multiple controls, to reduce the risk of unauthorized access or mishandling. This usually refers to encryption of your data - but it also is about controlling access.

This is mainly the same best practice advise as traditional AWS - encrypt all your storage at rest.

There are two places where you can (and should) optionally enable encryption for data at-rest with EKS:

- You can enable AWS KMS for envelope encryption of Kubernetes secrets

- You can enable encryption for any PersistentVolume via the CSI Driver

- For the EBS CSI Driver here is an example of enabling encryption

- This is one area where leveraging a 3rd party admission controller like OPA Gatekeeper can help you enforce things like people needing to use your StorageClass with encryption enabled

- And for the EFS CSI Driver, since it it doesn't create the EFS filesystem but uses an existing one, you need to ensure that you enabled encryption-at-rest when the filesystem was created

- For the EBS CSI Driver here is an example of enabling encryption

This is also the same as the traditional best practice in AWS - only the people or services that need access to the data should have it.

The difference is that there are two levels of abstraction with EKS - the Kubernetes view of the PersistentVolumes and the AWS view (as they turn into EBS or EFS etc. under the hood):

- Can you interactively

kubectl execinto the Pods that have them mounted through the encryption? - Can you access them via other Pods or via

sshing into the Node where they are mounted? - Can you 'steal' them by mounting them into another Pod?

- Can you 'steal' them by mounting them to another machine in AWS (including via snapshotting and then spinning up a new volume from the snapshot)

Most of these are controlled via Kubernetes RBAC. PersistentVolumes are Namespaced so doing the right thing there re: limiting who can access that Namespace (via not giving out ClusterRoles and ensuring only the 'right people' have Roles in the Namespace) mostly helps control access. The exceptions to that are:

- If you can

sshor onto the Node as root then you can do anything including get at the paths that all the PV is mounted under. So implementing tight controls over who can ssh onto cluster Nodes is important. - If you can escape your container via options such as hostPID and a privileged Security Context then you might be able to get to the place on the Node's disk where the data is mounted. So implementing PodSecurityAdmission and tightly controlling those options are important.

- If you have administrative access to AWS where you can re-mount the EBS/EFS volumes (or their snapshots) than you can circumvent the K8s controls via the lower-level AWS ones.

So controlling access to the Kubernetes API, to the Nodes as well as to the AWS API all have a role to play here.

This set of best practices is focused on protecting your data in transit by implementing multiple controls to reduce the risk of unauthorized access or loss. This usually refers to encryption of your data - but it also is about controlling access.

While the best practices here at a high level are the same as native AWS - that you want all your data in-transit to be encrypted - you have another of those strategic choices to make around how to do so with Kubernetes/EKS.

When using the AWS Load Balancer Controller and the AWS ALB you can choose to have it handle the encryption for you for HTTPS/TLS. The question then is whether you let the encryption terminate there or have it re-encrypted through to your workload. The thing that makes that easier to achieve is that the ALB doesn't verify the certificates of your workload - so you can enable HTTPS with a self-signed cert in your Pod, just covering the communication between the ALB and your Pod(s), and then have the ALB present the 'real' certificate to the clients.

The alternative is to use an AWS NLB and have it pass through the traffic all the way through to the Pod(s). In that case, you do need the Pod to present/own the 'real' certificate the clients will see. This can be orchestrated through the cert-manager operator for Kubernetes - making it fairly easy and automatic.

Kubernetes has long has the ability to manage load balancers, including to orchestrate their encryption, via Ingress. These were built to:

- Be plugable and standardized that the same Ingress manifests could be used regardless of the load balancer the customer chooses

- Have the chosen Ingress Controller provision and configure the load balancers automatically in response to what the users declare in their Ingress YAML manifests

Ingress has had a few challenges though:

- The manifest standard didn't have parameters that covered things like certificate management or LB-specific options - so you ended up with much of that being specified via annotations that varied from Ingress to Ingress - breaking the "write once run on any Ingress Controller" original goal

- That also meant that people were more likely to use things like the nginx Ingress controller even in AWS EKS because they wanted to be sure that the Ingress documents / IaC would work exactly the same if they were run outside of AWS

- It had some challenges around RBAC and namespacing (e.g. people in different Namespaces wanting to share a single LB with Ingress documents they control in their own Namespace)

Rather that 'fix' Ingress Kubernetes has just launched a replacement that addresses all the issues - the Gateway API. Today the AWS Load Balancer Controller doesn't yet support the Gateway API - but Ingress isn't going away for some time and I am sure it will before that is deprecated. Once it does support Gateway API then it might encourage you to use the native LBs in AWS knowing that the same IaC will run outside of AWS on something like nginx if you need it to later.

Another method of ensuring that your data is encrypted is to use a Service Mesh. The most common one used with Kubernetes is Istio - which is both opensource and a member of the CNCF.

This has traditionally put a 'sidecar' container running the Envoy proxy into each Pod, intercepted all the network traffic in/out and can ensure that it is encrypted without needing to change the workload.

It has many advanced capabilities including helping to automatically facilitate both mutual authentication and authorization between services via mTLS. Moving from an identity based on IPs or Kubernetes label to one based on certificates is a big step forward that is appealing to many security teams when it comes to protecting their data and services.

It is, however, an advanced/complex topic that is out of the scope of this WAR EKS lens.