Sometimes writing a solution recursively will make your code easier to read and reason about. Linked Lists can lend themselves well to recursion, because a clear base case is if the node is nil. We can use the following structure to traverse a Linked List recursively:

class ListNode<T> {

let val: T

var next: ListNode<T>?

init(val: T) {

self.val = val

}

}

func traverse<T>(_ node: ListNode<T>?, _ onVisit: (ListNode<T>) -> Void) {

guard let node = node else { return }

onVisit(node)

traverse(node.next, onVisit)

}

let aNode = ListNode(val: "A")

let bNode = ListNode(val: "B")

let cNode = ListNode(val: "C")

let dNode = ListNode(val: "D")

aNode.next = bNode

bNode.next = cNode

cNode.next = dNode

traverse(aNode) { (node) in print(node.val) }We can apply the same principle to solve the middle of the Linked List problem in the warm-up:

func middleNode(_ head: ListNode?) -> ListNode? {

let count = nodeCount(startingAt: head)

return getNode(atIndex: count / 2, startingAt: head)

}

func getNode(atIndex n: Int, startingAt head: ListNode?) -> ListNode? {

guard let head = head else { return nil }

guard n != 0 else { return head }

return getNode(atIndex: n - 1, startingAt: head.next)

}

func nodeCount(startingAt head: ListNode?) -> Int {

guard let head = head else { return 0 }

return 1 + nodeCount(startingAt: head.next)

}https://www.hackingwithswift.com/example-code/language/what-are-indirect-enums

Swift generally prefers not to use classes, and instead use structs or enums. However, we are not able to use a struct to define a Linked List Node. If you put the following into a Playground, you'll see the error below:

struct ListNode<T> {

let val: T

var next: ListNode<T>?

init(val: T) {

self.val = val

}

}

// Compile Time Error: Value type 'ListNode<T>' cannot have a stored property that recursively contains itBecause structs a value types a struct needs to allocate enough space to store all of its properties. But how much space will next take up? It doesn't know! You might have one node, or a thousand nodes in your list. A class works because it doesn't actually store the data inside of it, merely a reference to it. However, we can use a neat Swift trick to define a Linked List using an enum. This is unlikely to come up in an interview problem, but showcases a strong knowledge of Swift.

indirect enum ListNode<T> {

case tail(value: T)

case node(value: T, next: ListNode)

}

let tail = ListNode.tail(value: "D")

let cNode = ListNode.node(value: "C", next: tail)

let bNode = ListNode.node(value: "B", next: cNode)

let aNode = ListNode.node(value: "A", next: bNode)

func traverse<T>(node: ListNode<T>) {

switch node {

case let .tail(value):

print(value)

case let .node(value, next):

print(value)

traverse(node: next)

}

}

traverse(node: aNode)The indirect keyword tells the compiler that it shouldn't store the data directly, but keep a reference to it.

A very common solution to Linked List problems is to use two pointers that both iterate through the Linked List, one of them moving slower than the other. Let's apply that solution to our middle of a Linked List problem:

func middleNode(_ head: ListNode?) -> ListNode? {

var slow = head

var fast = head

while fast?.next != nil {

slow = slow?.next

fast = fast?.next?.next

}

return slow

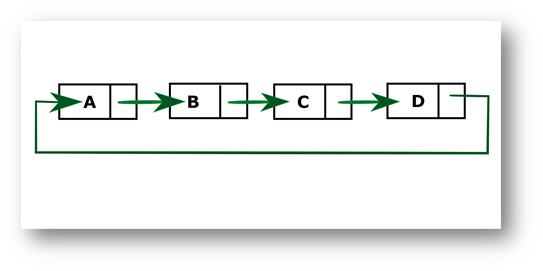

}Most Linked Lists that we've seen follow a straightforward linear path:

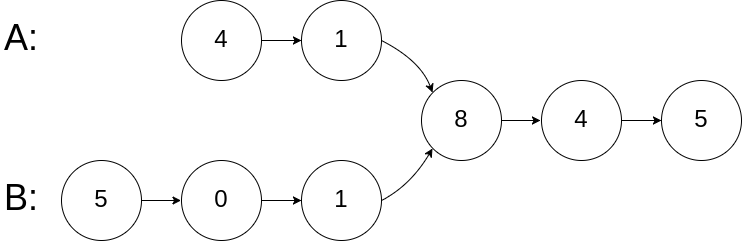

However, it's also possible for a Linked List to point to a Node that is part of another Linked List, or back to a previous node to create a cycle.

The most efficient way to detect a cycle in a Linked List is by using Floyd's algorithm (a utilization of the "runner" technique)