Let me start out by giving a nod to Jeff Atwood and Joel Spolsky for working tirelessly to help programmers get better and build better software. You'll note that many of the links on this page come from or are linked to from their blogs. Note: these are the guys that bring us [stack overflow](the Stack Exchange network of Q&A sites).

This page is an attempt to grab a few important links for my students in a semi-organized but nonexhaustive way.

For a bit of advice, you can also check out my Little Nybbles of Development Wisdom.

The way managers imagine software development with multiple programmers versus what happens in practice:

A modern example, Software glitches leave Navy Smart Ship dead in the water. The ship had to be towed into the Naval base at Norfolk, VA, because a database overflow caused its propulsion system to fail [snicker].

And How an ancient shipbuilding project failed.

For more examples of roadkill, see The Long, Dismal History of Software Project Failure

Steve McConnell, author of the famous Code Complete, wrote in Software Estimation: Demystifying the Black Art:

size is easily the most significant determinant of effort, cost, and schedule. The kind of software you're developing comes in second, and personnel factors are a close third. The programming language and environment you use are not first-tier influences on project outcome, but they are a first-tier influence on the estimate.

So, in order of importance to project "difficulty" or probability of failure:

- size (smaller is better obviously)

- type of software (xray machine? space probe? crappy website you and your little buddies make?)

- personnel factors (can't hire the right developers? Half the developers won't talk to the other half? many are working remotely?)

Why Software Fails is a great read and lists these as common reasons for failure:

- Unrealistic or unarticulated project goals

- Inaccurate estimates of needed resources

- Badly defined system requirements

- Poor reporting of the project's status

- Unmanaged risks

- Poor communication among customers, developers, and users

- Use of immature technology

- Inability to handle the project's complexity

- Sloppy development practices

- Poor project management

- Stakeholder politics

- Commercial pressures

Article quote:

All IT systems are intrinsically fragile. In a large brick building, you'd have to remove hundreds of strategically placed bricks to make a wall collapse. But in a 100,000-line software program, it takes only one or two bad lines to produce major problems. In 1991, a portion of AT&T's telephone network went out, leaving 12 million subscribers without service, all because of a single mistyped character in one line of code.

Bad decisions by project managers are probably the single greatest cause of software failures today.

If there's a theme that runs through the tortured history of bad software, it's a failure to confront reality.

Of course, we can easily start off on the wrong foot and dramatically increase chances of failure:

An article by Zef Hemel, Pick Your Battles, on how picking bleeding edge software can really make you bleed. There really is something to be said for proven technology even if it's not cool. The funny thing is that it's hard to hire developers if you're not doing the latest cool thing. I know one company that is starting to use Scala so they attract developers but still use proven Java technology. Zef says:

Go and build amazing applications. Build them with the most boring technology you can find. The stuff that has been in use for years and years.

This highlights why I have this critical rule from my Little Nybbles of Development Wisdom:

Do not rely on anybody else's software for your core application unless you really trust and have tested the library or service. If you have to use other software for a critical component, make sure you get the source.

(give epicentric story)

In that same article, I point out:

Programmers are curious beasts, which is normally a good thing. However, watch out that they don't find new technology X and demand to use it because "it's so cool." At the same time, don't let management force X on you to make your software buzzword compliant.

(hadoop-for-the-sake-of-hadoop, EJB example)

Why writing software is not like engineering. And a similar article You're not an engineer.

Why are software development estimates regularly off by a factor of 2-3 times?

Why do dynamic languages make it more difficult to maintain/develop large code bases?

Here is an interesting article on the effects of working long hours on productivity. It also addresses how you should seat your programmers and whether you should put the people with different roles together.

We've tried to fix it, which obviously didn't and doesn't work or we wouldn't be having this conversation.

Some slides on lifecycle management from University of Washington CSE403.

Some extremely experienced developers conclude the opposite of such "control freakism". For example, Real Ultimate Programming Power:

**In the absence of mentoring and apprenticeship**, the dissemination of better programming practices is often conveniently packaged into processes and methodologies.

He lists some of the key principles without going to some full-blown development religion...er...philosophy:

Another way to look at that is:

- Avoid code duplication

- Use the simplest possible thing that would work

- Don't design, implement, or include anything you don't need right now

I'd also add: Use as few machines and system components as possible.

But that's not enough structure for most developers; why? Let's begin by looking at what kind of developers there are.

(draw groups of developers for testing, architecture, coding, technical writing VS a group of developers that each do testing, architecture, coding, documentation. What kind of people to the various techniques work with? What kind of applications?)

Developers go through some fairly well-defined "development" as they acquire skill and experience. Slides taken from Developing Expertise: Herding Racehorses, Racing Sheep:

Level 1: Beginner

- Little or no previous experience

- Doesn't want to learn: wants to accomplish a goal

- No discretionary judgement

- Rigid adherence to rules

Level 2: Advanced Beginner

- Starts trying tasks on their own

- Has difficulty troubleshooting

- Wants information fast

- Can place some advice in context required

- Uses guidelines, but without holisitic understanding

Level 3: Competent

- Develops conceptual models

- Troubleshoots on their own

- Seeks out expert advice

- Sees actions at least partially in terms of long-term plans and goals

Level 4: Proficient

- Guided by maxims applied to the current situation

- Sees situations holistically

- Will self-correct based on previous performance

- Learns from the experience of others

- Frustrated by oversimplified information

Level 5: Expert

- No longer relies on rules, guidelines, or maxims

- Works primarily from intuition

- Analytic approaches only used in novel situations or when problems occur

- When forced to follow set rules, performance is degraded

Ok, so what is the relationship between methodologies and skill level? Level 5 means never having to say you're sorry:

I am not trying to encourage the level 5 means never having to say you're sorry attitude. "No rules" isn't shorthand for an air of smug superiority, although there's certainly no shortage of that in our profession. "No rules" means that we should actively seek out challenging development opportunities with lots of unknowns, work that takes considerable experience and skill. **The kind of work that cannot be done by beginners slavishly following a big-Em methodology**.

From Joel Spolsky, Why is it that some of the biggest IT consulting companies in the world do the worst work?:

The secret of Big Macs is that they're not very good, but every one is not very good in exactly the same way. ... Beware of Methodologies. They are a great way to bring everyone up to a dismal, but passable, level of performance, but at the same time, they are aggravating to more talented people who chafe at the restrictions that are placed on them.

Joel says that the higher you go up the levels in developerland, the lower the value of methodologies/rigid-rules.

How not to be outsourced/downsized? Don't be in a job that is governed by rules, because those are the easiest kinds of jobs to give to the lowest, i.e. cheapest, programmers.

Or, are there only Two Types of Programmers?

The 20% folks are what many would call “alpha” programmers — the leaders, trailblazers, trendsetters, the kind of folks that places like Google and Fog Creek software are obsessed with hiring. These folks were the first ones to install Linux at home in the 90′s; the people who write lisp compilers and learn Haskell on weekends “just for fun”; they actively participate in open source projects; they’re always aware of the latest, coolest new trends in programming and tools. ... The 80% folks make up the bulk of the software development industry. They’re not stupid; they’re merely vocational. They went to school, learned just enough Java/C#/C++, then got a job writing internal apps for banks, governments, travel firms, law firms, etc. The world usually never sees their software. They use whatever tools Microsoft hands down to them. ... Shocking statement #1: Most of the software industry is made up of 80% programmers. Yes, most of the world is small Windows development shops, or small firms hiring internal programmers.

In Mort, Elvis, Einstein, and You, Jeff Atwood was responding to negative feedback he got when he referenced the "two types of programmers" article: "the very act of commenting on an article about software development automatically means you're not a vocational eighty-percenter" and perhaps most importantly:

"The other eighty percent are not actively thinking about the craft of software development."

Many programmers I see are obsessed with learning "best practices", memorizing the gang of four patterns book, closely following development strategies. All this comes down to reading a bunch of bullshit instead of doing your job. It reminds me of a friend that I had in college. He would spend all of his time getting pencils and paper and other things together in order so that he could start the homework, but he never started the homework.

If you're not thinking about the process by which you develop software, the subject of this course, you're part of the 80% not 20%. Don't just write software. Think about how you write software or even write software to help you write software.

Parrt's control theory: You cannot control anybody or anything. You can only nudge or influence.

We are all panicked about risk and failing when developing large pieces of software, with good reason. In order to control the process, we come up with all kinds of measurements. Then we try to go the other way and control the process by coming up with rules or formulas based upon these measurements that must be satisfied. Hahahaha.

Remember that just because a metric is good, "improving" it too far is a bad thing. Your resting heartrate is considered a good proxy for overall health. Improving it down to zero is not recommended.

Also remember: Precision does not equal accuracy!

Tom DeMarco in Software Engineering: An Idea Whose Time Has Come and Gone? makes the analogy between controlling software development and controlling a teenager. Just because you can measure their height, grades, how many friends they have and so on doesn't mean that you can control them. Coming up with a rule that says: my child will have 10 good friends and get good grades is meaningless towards controlling that child.

In Software Engineering: Dead?, Jeff Atwood says "control is ultimately illusory on software development projects."

My style of development and testing is highly agile. I am agile in that I am prepared to question and rethink anything. I change and develop my methods. I may learn from packaged ideas like Extreme Programming, but I never follow them. Following is for novices who are under active supervision. Instead, I craft methods on a project by project basis, and I encourage other people to do that, as well. I take responsibility for my choices. That’s engineering for adults like us.

Guidelines, particularly in the absence of experts and mentors, are useful. But there's also a very real danger of hewing too slavishly to rulesets. Programmers are already quite systematic by disposition, so the idea that you can come up with a detailed enough set of rules, and sub-rules, and sub-sub-rules, that you can literally program yourself for success with a "system" of sufficient sophistication -- this, unfortunately, comes naturally to most software developers. If you're not careful, you might even slip and fall into a Methodology. Then you're in real trouble.

and

Rules, guidelines, and principles are gems of distilled experience that should be studied and respected. But they're never a substute for thinking critically about your work.

Bill de hora' 3 pillars:

...the **version control system** is a first order effect on software, along with two others--the **build system** and the **bugtracker**. Those choices impact absolutely everything else. Things like IDEs, by comparison, don't matter at all. Even choice of methodology might matter less. Although I'm betting there are plenty of software and management teams out there that see version control, build systems and bugtrackers as being incidental to the work, not mission critical tools.

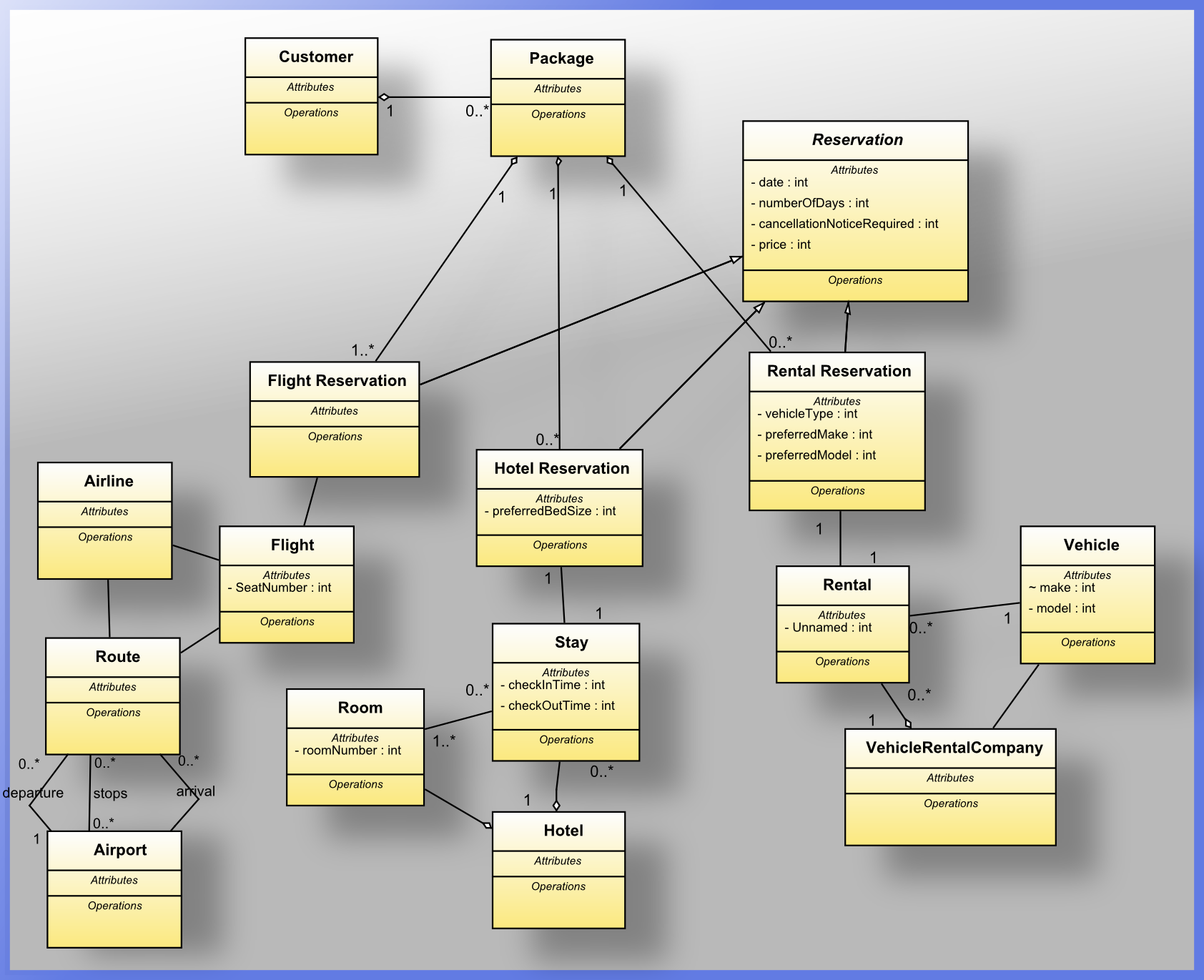

I certainly create lots of diagrams and write copious notes when designing software, but they are super informal. Why? Well, what is the difference between writing something out by hand and using a word processor? Speed vs precision. Precision at the UML diagram level provides a false sense of control over reality. Precision does not imply accuracy. It usually just means you are more precisely wrong. Ha! Besides we already have precision: it's called code.

Why formalize? I often use a graphics tool, but why bother with some ugly diagrams specified by committee? Just draw something that gets the idea across.

Large programming/IT shops for low-tech companies like phone companies and accounting firms often try to manage large software development by having so-called analysts design an application with UML down the object level and then have programmers simply translate the design to code and implement it like machines. This doesn't work for two reasons:

- there is no job satisfaction being the programmer, hence, you will not be able to hire good programmers

- when you actually try to code something, you often have to make radical changes in the design. Usually these programmers are largely ignored by the upper echelon of the hiearchy.

UML can create some pretty pictures and humans like to make these diagrams, but they are super fragile. Changes at the method and field variable name occur constantly forcing constant changes in the UML diagram. You've just created another full time job; that costs money and adds a serious parallel-update dependency.

When you have a huge UML diagram, people will often post this on a large wall so you can see how everything fits together and so on. Turns out that finding your classes and their relationships without a computer is pretty tough as you need to put fingers down at lots of different locations to "hold your place" kind of like a twister game.

One of the reasons I get away with not using lots of formal diagrams is that I go to great lengths to write code that is very easy to understand from the overall level and the very specific.

In summary, diagrams should be as high level as possible given their intended use. Precision should be relegated to the code level. This isolates the design more from implementation detail changes. A semi-formal diagram is often useful, however, for communication with fellow programmers or dumbing things down for management. You can get totally caught up building pretty pictures rather than actually building something.

StoreItems: {Book, Map, Paper, Pen, Stapler}

Book ->* Chapter or Person ->+ address or Person->Employer

Really great example is a state diagram for HTML web pages:

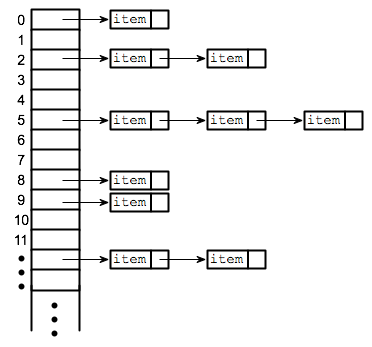

Similar to assocation diagrams, but specifically designed to show a formal data structure like List of List or Hashtable of Hashtable (useful for example, to do insertion sort; can alter a value and place in new location in constant time; kinda like radix sort).

It helps to design algorithms if you can see the structure; you can say "ok, I'm here and I decide to walk here based on this" etc...

People doing research on software engineering seem to ignore the importance of specific algorithm design. jGuru has some fairly hairy algorithms for doing document analysis etc... that had to be designed with data structure diagrams. Tied into overall diagram then with words like "compute histogram", "Lexicon", etc...