| title | thumbnail | authors | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

AudioLDM 2, but faster ⚡️ |

/blog/assets/161_audioldm2/thumbnail.png |

|

AudioLDM 2 was proposed in AudioLDM 2: Learning Holistic Audio Generation with Self-supervised Pretraining by Haohe Liu et al. AudioLDM 2 takes a text prompt as input and predicts the corresponding audio. It can generate realistic sound effects, human speech and music.

While the generated audios are of high quality, running inference with the original implementation is very slow: a 10 second audio sample takes upwards of 30 seconds to generate. This is due to a combination of factors, including a deep multi-stage modelling approach, large checkpoint sizes, and un-optimised code.

In this blog post, we showcase how to use AudioLDM 2 in the Hugging Face 🧨 Diffusers library, exploring a range of code optimisations such as half-precision, flash attention, and compilation, and model optimisations such as scheduler choice and negative prompting, to reduce the inference time by over 10 times, with minimal degradation in quality of the output audio. The blog post is also accompanied by a more streamlined Colab notebook, that contains all the code but fewer explanations.

Read to the end to find out how to generate a 10 second audio sample in just 1 second!

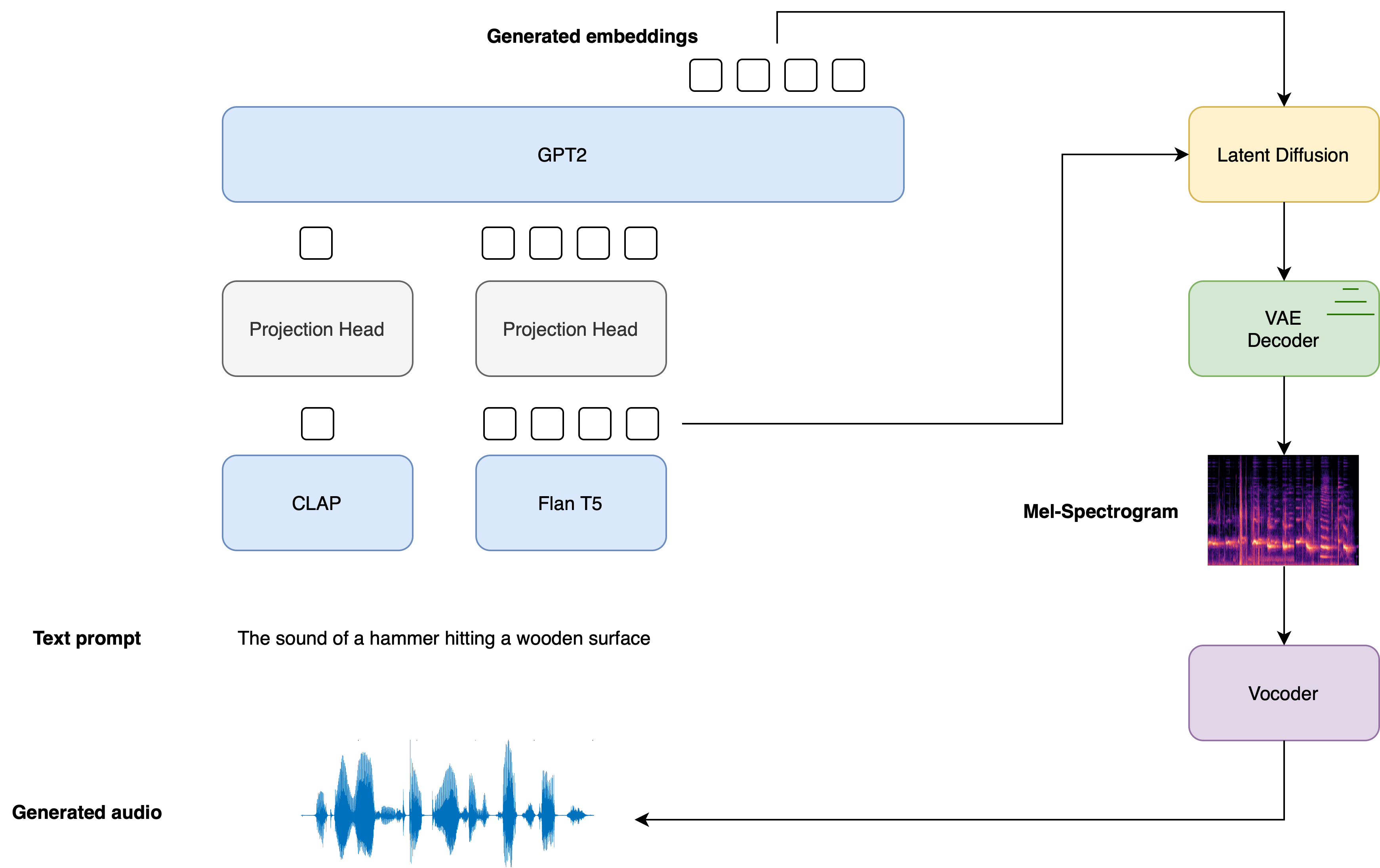

Inspired by Stable Diffusion, AudioLDM 2 is a text-to-audio latent diffusion model (LDM) that learns continuous audio representations from text embeddings.

The overall generation process is summarised as follows:

- Given a text input \(\boldsymbol{x}\), two text encoder models are used to compute the text embeddings: the text-branch of CLAP, and the text-encoder of Flan-T5

$$ \boldsymbol{E}{1} = \text{CLAP}\left(\boldsymbol{x} \right); \quad \boldsymbol{E}{2} = \text{T5}\left(\boldsymbol{x}\right) $$

The CLAP text embeddings are trained to be aligned with the embeddings of the corresponding audio sample, whereas the Flan-T5 embeddings give a better representation of the semantics of the text.

- These text embeddings are projected to a shared embedding space through individual linear projections:

$$ \boldsymbol{P}{1} = \boldsymbol{W}{\text{CLAP}} \boldsymbol{E}{1}; \quad \boldsymbol{P}{2} = \boldsymbol{W}{\text{T5}}\boldsymbol{E}{2} $$

In the diffusers implementation, these projections are defined by the AudioLDM2ProjectionModel.

- A GPT2 language model (LM) is used to auto-regressively generate a sequence of \(N\) new embedding vectors, conditional on the projected CLAP and Flan-T5 embeddings:

$$ \tilde{\boldsymbol{E}}{i} = \text{GPT2}\left(\boldsymbol{P}{1}, \boldsymbol{P}{2}, \tilde{\boldsymbol{E}}{1:i-1}\right) \qquad \text{for } i=1,\dots,N $$

- The generated embedding vectors \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{E}}{1:N}\) and Flan-T5 text embeddings \(\boldsymbol{E}{2}\) are used as cross-attention conditioning in the LDM, which de-noises a random latent via a reverse diffusion process. The LDM is run in the reverse diffusion process for a total of \(T\) inference steps:

$$ \boldsymbol{z}{t} = \text{LDM}\left(\boldsymbol{z}{t-1} | \tilde{\boldsymbol{E}}{1:N}, \boldsymbol{E}{2}\right) \qquad \text{for } t = 1, \dots, T $$

where the initial latent variable \(\boldsymbol{z}{0}\) is drawn from a normal distribution \(\mathcal{N} \left(\boldsymbol{0}, \boldsymbol{I} \right)\). The UNet of the LDM is unique in the sense that it takes two sets of cross-attention embeddings, \(\tilde{\boldsymbol{E}}{1:N}\) from the GPT2 language model and \(\boldsymbol{E}_{2}\) from Flan-T5, as opposed to one cross-attention conditioning as in most other LDMs.

- The final de-noised latents \(\boldsymbol{z}_{T}\) are passed to the VAE decoder to recover the Mel spectrogram \(\boldsymbol{s}\):

$$ \boldsymbol{s} = \text{VAE}{\text{dec}} \left(\boldsymbol{z}{T}\right) $$

- The Mel spectrogram is passed to the vocoder to obtain the output audio waveform \(\mathbf{y}\):

The diagram below demonstrates how a text input is passed through the text conditioning models, with the two prompt embeddings used as cross-conditioning in the LDM:

For full details on how the AudioLDM 2 model is trained, the reader is referred to the AudioLDM 2 paper.

Hugging Face 🧨 Diffusers provides an end-to-end inference pipeline class AudioLDM2Pipeline that wraps this multi-stage generation process into a single callable object, enabling you to generate audio samples from text in just a few lines of code.

AudioLDM 2 comes in three variants. Two of these checkpoints are applicable to the general task of text-to-audio generation. The third checkpoint is trained exclusively on text-to-music generation. See the table below for details on the three official checkpoints, which can all be found on the Hugging Face Hub:

| Checkpoint | Task | Model Size | Training Data / h |

|---|---|---|---|

| cvssp/audioldm2 | Text-to-audio | 1.1B | 1150k |

| cvssp/audioldm2-music | Text-to-music | 1.1B | 665k |

| cvssp/audioldm2-large | Text-to-audio | 1.5B | 1150k |

Now that we've covered a high-level overview of how the AudioLDM 2 generation process works, let's put this theory into practice!

For the purposes of this tutorial, we'll initialise the pipeline with the pre-trained weights from the base checkpoint,

cvssp/audioldm2. We can load the entirety of the pipeline using the

.from_pretrained

method, which will instantiate the pipeline and load the pre-trained weights:

from diffusers import AudioLDM2Pipeline

model_id = "cvssp/audioldm2"

pipe = AudioLDM2Pipeline.from_pretrained(model_id)Output:

Loading pipeline components...: 100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 11/11 [00:01<00:00, 7.62it/s]

The pipeline can be moved to the GPU in much the same way as a standard PyTorch nn module:

pipe.to("cuda");Great! We'll define a Generator and set a seed for reproducibility. This will allow us to tweak our prompts and observe the effect that they have on the generations by fixing the starting latents in the LDM model:

import torch

generator = torch.Generator("cuda").manual_seed(0)Now we're ready to perform our first generation! We'll use the same running example throughout this notebook, where we'll

condition the audio generations on a fixed text prompt and use the same seed throughout. The audio_length_in_s

argument controls the length of the generated audio. It defaults to the audio length that the LDM was trained on

(10.24 seconds):

prompt = "The sound of Brazilian samba drums with waves gently crashing in the background"

audio = pipe(prompt, audio_length_in_s=10.24, generator=generator).audios[0]Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 200/200 [00:13<00:00, 15.27it/s]

Cool! That run took about 13 seconds to generate. Let's have a listen to the output audio:

from IPython.display import Audio

Audio(audio, rate=16000)Sounds much like our text prompt! The quality is good, but still has artefacts of background noise. We can provide the

pipeline with a negative prompt

to discourage the pipeline from generating certain features. In this case, we'll pass a negative prompt that discourages

the model from generating low quality audio in the outputs. We'll omit the audio_length_in_s argument and leave it to

take its default value:

negative_prompt = "Low quality, average quality."

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 200/200 [00:12<00:00, 16.50it/s]

The inference time is un-changed when using a negative prompt \({}^1\); we simply replace the unconditional input to the LDM with the negative input. That means any gains we get in audio quality we get for free.

Let's take a listen to the resulting audio:

Audio(audio, rate=16000)There's definitely an improvement in the overall audio quality - there are less noise artefacts and the audio generally sounds sharper.

\({}^1\) Note that in practice, we typically see a reduction in inference time going from our first generation to our second. This is due to a CUDA "warm-up" that occurs the first time we run the computation. The second generation is a better benchmark for our actual inference time.

PyTorch 2.0 and upwards includes an optimised and memory-efficient implementation of the attention operation through the

torch.nn.functional.scaled_dot_product_attention (SDPA) function. This function automatically applies several in-built optimisations depending on the inputs, and runs faster and more memory-efficient than the vanilla attention implementation. Overall, the SDPA function gives similar behaviour to flash attention, as proposed in the paper Fast and Memory-Efficient Exact Attention with IO-Awareness by Dao et. al.

These optimisations will be enabled by default in Diffusers if PyTorch 2.0 is installed and if torch.nn.functional.scaled_dot_product_attention

is available. To use it, just install torch 2.0 or higher as per the official instructions,

and then use the pipeline as is 🚀

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 200/200 [00:12<00:00, 16.60it/s]

For more details on the use of SDPA in diffusers, refer to the corresponding documentation.

By default, the AudioLDM2Pipeline loads the model weights in float32 (full) precision. All the model computations are

also performed in float32 precision. For inference, we can safely convert the model weights and computations to float16

(half) precision, which will give us an improvement to inference time and GPU memory, with an impercivable change to

generation quality.

We can load the weights in float16 precision by passing the torch_dtype

argument to .from_pretrained:

pipe = AudioLDM2Pipeline.from_pretrained(model_id, torch_dtype=torch.float16)

pipe.to("cuda");Let's run generation in float16 precision and listen to the audio outputs:

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]

Audio(audio, rate=16000)Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 200/200 [00:09<00:00, 20.94it/s]

The audio quality is largely un-changed from the full precision generation, with an inference speed-up of about 2 seconds.

In our experience, we've not seen any significant audio degradation using diffusers pipelines with float16 precision,

but consistently reap a substantial inference speed-up. Thus, we recommend using float16 precision by default.

To get an additional speed-up, we can use the new torch.compile feature. Since the UNet of the pipeline is usually the

most computationally expensive, we wrap the unet with torch.compile, leaving the rest of the sub-models (text encoders

and VAE) as is:

pipe.unet = torch.compile(pipe.unet, mode="reduce-overhead", fullgraph=True)After wrapping the UNet with torch.compile the first inference step we run is typically going to be slow, due to the

overhead of compiling the forward pass of the UNet. Let's run the pipeline forward with the compilation step get this

longer run out of the way. Note that the first inference step might take up to 2 minutes to compile, so be patient!

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 200/200 [01:23<00:00, 2.39it/s]

Great! Now that the UNet is compiled, we can now run the full diffusion process and reap the benefits of faster inference:

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 200/200 [00:04<00:00, 48.98it/s]

Only 4 seconds to generate! In practice, you will only have to compile the UNet once, and then get faster inference for

all successive generations. This means that the time taken to compile the model is amortised by the gains in subsequent

inference time. For more information and options regarding torch.compile, refer to the

torch compile docs.

Another option is to reduce the number of inference steps. Choosing a more efficient scheduler can help decrease the

number of steps without sacrificing the output audio quality. You can find which schedulers are compatible with the

AudioLDM2Pipeline by calling the schedulers.compatibles

attribute:

pipe.scheduler.compatiblesOutput:

[diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_lms_discrete.LMSDiscreteScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_k_dpm_2_discrete.KDPM2DiscreteScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_dpmsolver_multistep.DPMSolverMultistepScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_unipc_multistep.UniPCMultistepScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_euler_discrete.EulerDiscreteScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_pndm.PNDMScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_dpmsolver_singlestep.DPMSolverSinglestepScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_heun_discrete.HeunDiscreteScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_ddpm.DDPMScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_deis_multistep.DEISMultistepScheduler,

diffusers.utils.dummy_torch_and_torchsde_objects.DPMSolverSDEScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_ddim.DDIMScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_k_dpm_2_ancestral_discrete.KDPM2AncestralDiscreteScheduler,

diffusers.schedulers.scheduling_euler_ancestral_discrete.EulerAncestralDiscreteScheduler]

Alright! We've got a long list of schedulers to choose from 📝. By default, AudioLDM 2 uses the DDIMScheduler,

and requires 200 inference steps to get good quality audio generations. However, more performant schedulers, like DPMSolverMultistepScheduler,

require only 20-25 inference steps to achieve similar results.

Let's see how we can switch the AudioLDM 2 scheduler from DDIM to DPM Multistep. We'll use the ConfigMixin.from_config()

method to load a DPMSolverMultistepScheduler

from the configuration of our original DDIMScheduler:

from diffusers import DPMSolverMultistepScheduler

pipe.scheduler = DPMSolverMultistepScheduler.from_config(pipe.scheduler.config)Let's set the number of inference steps to 20 and re-run the generation with the new scheduler. Since the shape of the LDM latents are un-changed, we don't have to repeat the compilation step:

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, num_inference_steps=20, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 20/20 [00:00<00:00, 49.14it/s]

That took less than 1 second to generate the audio! Let's have a listen to the resulting generation:

Audio(audio, rate=16000)More or less the same as our original audio sample, but only a fraction of the generation time! 🧨 Diffusers pipelines are designed to be composable, allowing you two swap out schedulers and other components for more performant counterparts with ease.

The length of the audio sample we want to generate dictates the width of the latent variables we de-noise in the LDM. Since the memory of the cross-attention layers in the UNet scales with sequence length (width) squared, generating very long audio samples might lead to out-of-memory errors. Our batch size also governs our memory usage, controlling the number of samples that we generate.

We've already mentioned that loading the model in float16 half precision gives strong memory savings. Using PyTorch 2.0 SDPA also gives a memory improvement, but this might not be suffienct for extremely large sequence lengths.

Let's try generating an audio sample 2.5 minutes (150 seconds) in duration. We'll also generate 4 candidate audios by

setting num_waveforms_per_prompt=4.

Once num_waveforms_per_prompt>1,

automatic scoring is performed between the generated audios and the text prompt: the audios and text prompts are embedded

in the CLAP audio-text embedding space, and then ranked based on their cosine similarity scores. We can access the 'best'

waveform as that in position 0.

Since we've changed the width of the latent variables in the UNet, we'll have to perform another torch compilation step with the new latent variable shapes. In the interest of time, we'll re-load the pipeline without torch compile, such that we're not hit with a lengthy compilation step first up:

pipe = AudioLDM2Pipeline.from_pretrained(model_id, torch_dtype=torch.float16)

pipe.to("cuda")

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, num_waveforms_per_prompt=4, audio_length_in_s=150, num_inference_steps=20, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]Output:

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

OutOfMemoryError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-33-c4cae6410ff5> in <cell line: 5>()

3 pipe.to("cuda")

4

----> 5 audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, num_waveforms_per_prompt=4, audio_length_in_s=150, num_inference_steps=20, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]

23 frames

/usr/local/lib/python3.10/dist-packages/torch/nn/modules/linear.py in forward(self, input)

112

113 def forward(self, input: Tensor) -> Tensor:

--> 114 return F.linear(input, self.weight, self.bias)

115

116 def extra_repr(self) -> str:

OutOfMemoryError: CUDA out of memory. Tried to allocate 1.95 GiB. GPU 0 has a total capacty of 14.75 GiB of which 1.66 GiB is free. Process 414660 has 13.09 GiB memory in use. Of the allocated memory 10.09 GiB is allocated by PyTorch, and 1.92 GiB is reserved by PyTorch but unallocated. If reserved but unallocated memory is large try setting max_split_size_mb to avoid fragmentation. See documentation for Memory Management and PYTORCH_CUDA_ALLOC_CONF

Unless you have a GPU with high RAM, the code above probably returned an OOM error. While the AudioLDM 2 pipeline involves several components, only the model being used has to be on the GPU at any one time. The remainder of the modules can be offloaded to the CPU. This technique, called CPU offload, can reduce memory usage, with a very low penalty to inference time.

We can enable CPU offload on our pipeline with the function enable_model_cpu_offload():

pipe.enable_model_cpu_offload()Running generation with CPU offload is then the same as before:

audio = pipe(prompt, negative_prompt=negative_prompt, num_waveforms_per_prompt=4, audio_length_in_s=150, num_inference_steps=20, generator=generator.manual_seed(0)).audios[0]Output:

100%|███████████████████████████████████████████| 20/20 [00:36<00:00, 1.82s/it]

And with that, we can generate four samples, each of 150 seconds in duration, all in one call to the pipeline! Using the large AudioLDM 2 checkpoint will result in higher overall memory usage than the base checkpoint, since the UNet is over twice the size (750M parameters compared to 350M), so this memory saving trick is particularly beneficial here.

In this blog post, we showcased four optimisation methods that are available out of the box with 🧨 Diffusers, taking the generation time of AudioLDM 2 from 14 seconds down to less than 1 second. We also highlighted how to employ memory saving tricks, such as half-precision and CPU offload, to reduce peak memory usage for long audio samples or large checkpoint sizes.

Blog post by Sanchit Gandhi. Many thanks to Vaibhav Srivastav and Sayak Paul for their constructive comments. Spectrogram image source: Getting to Know the Mel Spectrogram. Waveform image source: Aalto Speech Processing.