npm install traits.js

Then:

var Trait = require('traits.js');OR

<script src="https://unpkg.com/traits.js@1/dist/traits.min.js"></script>traits.js is a Javascript library for Trait composition, as originally proposed in [1] but closer to the object-based, lexically nestable traits defined in [2]. The library has been designed for Ecmascript 5.1, but should be backwards-compatible with existing Ecmascript 3 implementations.

See also: API | Tutorial | howtonode article | Paper

Traits were originally defined as 'composable units of behavior' [1]: reusable groups of methods that can be composed together to form a class. Their purpose is to enable reuse of methods across class hierarchies. Single-inheritance class hierarchies often suffer from methods being duplicated across the hierarchy, because a class cannot inherit methods from two separate sources.

Traits may provide and require a number of methods. Required methods are like abstract methods in OO class hierarchies: their implementation should be provided by another trait or class. For example, "enumerability" of a collection object can be encoded as a trait providing all kinds of higher-order methods on collections based on a single method each that returns successive elements of the collection (cf. Ruby's Enumerable module) (in pseudo-code for clarity):

trait Enumerable {

provide {

map: function(fun) { var r = []; this.each(function (e) { r.push(fun(e)); }); return r; },

inject: function(init, accum) { var r = init; this.each(function (e) { r = accum(r,e); }); return r; },

...

}

require {

each: function(fun);

}

}

class Range(from, to) extends Object uses Enumerable {

function each(fun) { for (var i = from; i < to; i++) { fun(i); } }

}

var r = new Range(0,5);

r.inject(0,function(a,b){return a+b;}); // 10

In a language with both traits and classes, traits cannot be instantiated directly into objects. Rather, they are used to factor out and compose reusable sets of methods into a class. Traits can be recursively composed into larger, but possibly still incomplete, traits. Classes can be composed from zero or more traits. Classes, unlike traits, must be complete (or remain abstract). Traits cannot be composed by means of inheritance, but a class composed of one or more traits can take part in single inheritance. Methods provided by traits then override methods inherited from its superclass.

The main difference between traits and alternative composition techniques such as multiple inheritance and mixins is that upon trait composition, name conflicts (a.k.a. name clashes) should be explicitly resolved by the composer. This is in contrast to mixins and multiple inheritance, which define various kinds of linearization schemes that impose an implicit precedence on the composed entities, with one entity overriding all of the methods of another entity. While such systems often work well in small reuse scenarios, they are not robust: small changes in the ordering of mixins/classes somewhere high up in the inheritance/mixin chain may impact the way name clashes are resolved further down the inheritance/mixin chain. In addition, the linearization imposed by mixins/multiple inheritance precludes a composer to give precedence to both a method m1 from one mixin/class A and a method m2 from another mixin/class B: either all of A's methods take precedence over B, or all of B's methods take precedence over A.

Traits allow a composing entity to resolve name clashes in the individual components by either excluding a method from one of the components or by having one trait explicitly override the methods of another one. In addition, the composer may define an alias for a method, allowing the composer to refer to the original method even if its original name was excluded or overridden.

Name clashes that are never explicitly resolved will eventually lead to a composition error when traits are composed with a class. Depending on the language, this composition error may be a compile-time error, a runtime error when the class is composed, or a runtime error when a conflicting name is invoked on a class instance.

Trait composition is declarative in the sense that the ordering of composed traits does not matter. In other words, unlike mixins/multiple inheritance, trait composition is commutative and associative. This tremendously reduces the cognitive burden of reasoning about deeply nested levels of trait composition. In languages that support traits as a compile-time entity (similar to classes), trait composition can be entirely performed at compile-time, effectively "flattening" the composition and eliminating any composition overhead at runtime.

Since their publication in 2003, traits have received widespread adoption in the PL community, although the details of the many traits implementations differ significantly from the original implementation defined for Smalltalk. Traits have been adopted in Perl (see e.g. the Class::Trait module), Fortress, PLT Scheme [4], Slate, ... Scala supports "traits", although these should have been called mixins (there is no explicit conflict resolution). Traits are also considered for inclusion in PHP.

The above Enumerable example can be encoded using traits.js as follows:

var EnumerableTrait = Trait({

each: Trait.required, // should be provided by the composite

map: function(fun) { var r = []; this.each(function (e) { r.push(fun(e)); }); return r; },

inject: function(init, accum) { var r = init; this.each(function (e) { r = accum(r,e); }); return r; },

...

});

function Range(from, to) {

return Trait.create(

Object.prototype,

Trait.compose(

EnumerableTrait,

Trait({

each: function(fun) { for (var i = from; i < to; i++) { fun(i); } }

})));

}

var r = Range(0,5);

r.inject(0,function(a,b){return a+b;}); // 10traits.js represents traits as "property descriptor maps": objects whose keys represent property names and whose values are Ecmascript 5 "property descriptors" (this is the same data format as the one accepted by the standard ES5 functions Object.create and Object.defineProperties). Like classes, traits describe object structure and can be instantiated into runtime objects.

Basic traits can be created from simple object descriptions (usually Javascript object literals) and further composed into 'composite' traits using a small set of composition functions (explained below). In order to use a (composite) trait, it must be "instantiated" into an object. When a trait is instantiated into an object o, the binding of the this pseudovariable within the trait's methods will refer to o. If a trait T defines a method m that requires (depends on) the method r, m should call this method using this.r(...), and if that method was provided by some other trait, it will be found in the composite object o. The lexical scope of composed trait methods remains unaffected by trait composition.

As mentioned in the background, trait composition is orthogonal to inheritance. traits.js does not expect traits to take part in object-inheritance (i.e. prototype delegation) and should only be composed via trait composition. Traits do not have a "prototype", but the objects they instantiate do, and these objects may take part in object-inheritance.

traits.js exports a single variable, named Trait, bound to a function object. Calling Trait({...}) creates and returns a new trait. Furthermore, Trait defines the following properties:

requiredcompose(trait1, trait2, ..., traitN) -> traitresolve({ oldName: 'newName', nameToExclude: undefined, ... }, trait) -> traitoverride(trait1, trait2, ... , traitN) -> traiteqv(trait1, trait2) -> booleancreate(proto, trait) -> objectobject(record) -> object

Trait.required is a special singleton value that is used to denote missing required properties (see later). All of the methods defined on Trait are pure: they never modify their argument values and they do not depend on mutable state across invocations.

The function Trait.eqv(t1,t2) returns true if and only if t1 and t2 are equivalent. Two traits are equivalent if they describe the same set of property names, and the property descriptors bound to these names have identical attributes.

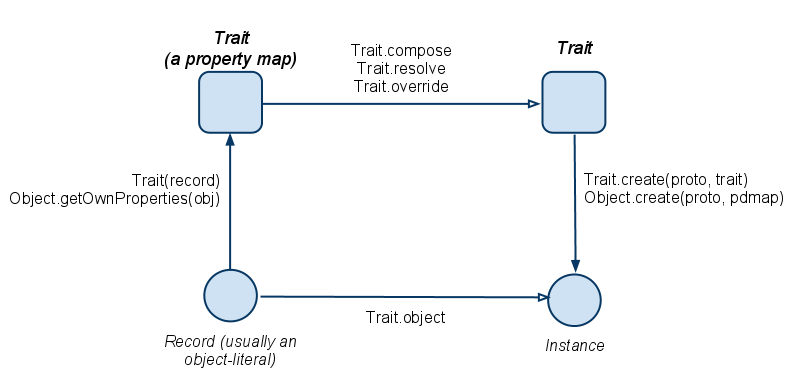

The following figure depicts the operations exported by the library:

Both the circles and the rounded squares are Javascript objects, but they are intended to be used in very different ways.

The Trait function acts as a constructor for simple (non-composite) traits. It essentially turns an object describing a record of properties into a trait. For example:

var T = Trait({

a: Trait.required,

b: function() { ... this.a() ... },

c: function() { ... }

});In traits.js, required properties are defined as data properties bound to a distinguished singleton Trait.required object. traits.js recognizes such data properties as required properties and they are treated specially by Trait.create and by Trait.compose (see later). Traits are not required to state their required properties explicitly.

The trait T provides the properties b and c and requires the property a. The Trait constructor converts the object literal into the following property descriptor map representing the trait:

{ 'a' : {

value: undefined,

required: true,

enumerable: false

},

'b' : {

value: function() { ... }, // note: value.prototype is frozen

method: true,

enumerable: true

},

'c' : {

value: function() { ... }, // note: value.prototype is frozen

method: true,

enumerable: true

}

}The attributes required and method are not standard ES5 attributes, but are interpreted by the traits.js library.

The objects passed to Trait should normally only serve as plain records that describe a simple trait's properties. We expect them to be used mostly in conjunction with Javascript's excellent object literal syntax. The Trait function turns an object into a property descriptor map with the following constraints:

-

Only the object's own properties are turned into trait properties (its prototype is not significant).

-

Data properties in the object record bound to the special

Trait.requiredsingleton are bound to a distinct "required" property descriptor (as shown above). -

Data properties in the object record bound to functions are interpreted as "methods". In order to ensure integrity, methods are distinguished from plain Javascript functions by

traits.jsin the following ways:-

The methods and the value of their

.prototypeproperty are frozen. -

Methods are 'bound' to an object at instantiation time (see later). The binding of

thisin the method's body is bound to the instantiated object.

-

-

Traitis a pure function if no other code has a reference to any of the object record's methods. IfTraitis applied to an object literal whose methods are represented as anonymous in-place functions as recommended, this should be the case.

The function Trait.compose is the workhorse of traits.js. It composes zero or more traits into a single composite trait. For example:

var T1 = Trait({ a: 0, b: 1});

var T2 = Trait({ a: 1, c: 2});

var Tc = Trait.compose(T1,T2);The composite trait contains all of the own properties of all of the argument traits (including non-enumerable properties). For properties that appear in multiple argument traits, a distinct "conflicting" property is defined in the composite trait. Tc will have the following structure:

{ 'a' : {

get: <conflict>,

set: <conflict>,

conflict: true

},

'b' : { value: 1 },

'c' : { value: 2 } }When compose encounters a property name that is defined by two or more argument traits, it marks the resulting property in the composite trait as a "conflicting property" by means of the conflict: true atrribute (again, this is not a standard ES5 attribute). Conflicting properties are accessor properties whose get and set methods (denoted using <conflict> above) raise an appropriate runtime exception when invoked.

Two properties p1 and p2 with the same name are not in conflict if:

-

p1orp2is arequiredproperty. If eitherp1orp2is a non-required property, therequiredproperty is overridden by the non-required property. -

p1andp2denote the "same" property. Two properties are considered to be the same if they refer to the same values and have the same attributes. This implies that it is OK for properties to be "inherited" via multiple composition paths from the same trait (cf. diamond inheritance:T1 = Trait.compose(T2,T3)whereT2 = Trait.compose(T4,...)andT3 = Trait.compose(T4, ...).

compose is a commutative and associative operation: the ordering of its arguments does not matter, and compose(t1,t2,t3) is equivalent to, for example, compose(t1,compose(t2,t3)) or compose(compose(t2,t1),t3).

The Trait.resolve "operator" can be used to resolve conflicts created by Trait.compose. The function takes as its first argument an object that can avoid conflicts either by renaming or by excluding property names. The object serves as a map, mapping a property name to either a string (indicating that the property should be renamed) or to undefined (indicating that the property should be excluded). For example, if we wanted to avoid the conflict in the Tc trait from the previous example, we could have composed T1 and T2 as follows:

var Trenamed = Trait.compose(T1, Trait.resolve({ a: 'd' }, T2);

var Texclude = Trait.compose(T1, Trait.resolve({ a: undefined }, T2);Trenamed now has the following structure:

{ 'a' : { value: 0 },

'b' : { value: 1 },

'c' : { value: 2 },

'd' : { value: 1 } } // T2.a renamed to 'd'Texclude has the structure:

{ 'a' : { value: 0 },

'b' : { value: 1 },

'c' : { value: 2 } }

// T2.a is excludedThe Trait.resolve operator is neutral with respect to required properties: renaming or excluding a required property has no effect.

When a property foo is renamed or excluded, foo is bound to Trait.required, to attest that the trait is not valid unless the composer provides a property for the old name. This is because methods in the renamed trait may internally still contain this.foo expressions. The renaming performed by resolve is shallow: it only changes the name property name, it will not change references to the original property name within other methods. This is analogous to the way method overriding works in standard inheritance schemes: overriding a method does not affect calls to the overridden method.

resolve subsumes the "alias" and "exclude" operators from the original traits model. However, whereas aliasing adds an additional name for the same method in a trait, the resolve operator renames the property, implicitly removing the old binding for the name and turning it into a required property. We have found this to be a more useful operator to resolve conflicts. If you really want to introduce an alias for a property, that can still be done as follows:

var Talias = Trait.compose(T1,

Trait.resolve({ a: 'd' }, T2),

Trait({ a: this.d })

);In this case, a is renamed to d by Trait.resolve and a new property a is added that refers to the renamed property.

Conflicts can also be resolved by means of overriding. The Trait.override function takes any number of traits and returns a composite trait containing all properties of its argument traits. In contrast to compose, override does not generate conflicts upon name clashes, but rather overrides the conflicting property with that of a trait with higher precedence. Trait precedence is from left to right, i.e. the properties of the first argument to override are never overridden. For example:

var Toverride = Trait.override(T1, T2);Toverride is equivalent to:

{ 'a' : { value: 0 }, // T1.a overrides T2.a

'b' : { value: 1 },

'c' : { value: 2 } }override is obviously not commutative, but it is associative, i.e. override(t1,t2,t3) is equivalent to override(t1,override(t2,t3)) or to override(override(t1,t2),t3). Composition via override most closely resembles the kind of composition provided by single-inheritance subclassing.

Since traits are just property maps, they can simply be instantiated by calling the ES5 built-in function Object.create. Of course, this built-in function does not know about the semantics of "required", "conflicting" and "method" properties. Required properties will be present in the instantiated object as non-enumerable data properties bound to undefined. Conflicting properties will be present as accessor properties that throw when accessed. Method properties will be present as plain data properties bound to functions.

The traits.js library additionally provides a function Trait.create, analogous to the built-in Object.create, to instantiate a trait into an object. The call Trait.create(proto, trait) creates and returns a new object o that inherits from proto and that has all of the properties described by the argument trait. Additionally:

-

an exception is thrown if 'trait' contains

requiredproperties. -

an exception is thrown if 'trait' contains

conflictproperties. -

the instantiated object and all of its accessor and method properties are frozen.

-

the

thispseudovariable in all accessors and methods of the object is bound to the instantiated object.

For example, calling Trait.create(Object.prototype, Toverride) results in an object that inherits from Object.prototype and has a structure as if defined by:

Object.freeze({

a: 0,

b: 1,

c: 2

})Use Trait.create to instantiate objects that should be considered "final" and complete. Use Object.create to instantiate objects that can remain "abstract" or otherwise extensible. For "final" objects, as generated by Trait.create, keep in mind that the this pseudovariable within their methods is bound at instantiation time to the instantiated object. This implies that final objects don't play nice with objects that delegate to them (this is no longer late bound for such objects). That's why we call them final: such objects should not serve as the prototype of other objects.

The method Trait.object is a convenient shorthand for writing "object literals" described by a trait. The call Trait.object({...}) is equivalent to the call Trait.create(Object.prototype, Trait({...})). Since Trait.create generates high-integrity objects, Trait.object({...}) can be thought of as "high-integrity-object-literal" syntax. Such objects are frozen, their methods are frozen, their methods' prototypes are frozen, and their this pseudovariable cannot be rebound by clients.

Traits were originally defined as stateless collections of methods only. traits.js allows stateful traits and allows traits to describe any Javascript property, regardless of whether it contains a function and regardless of whether it is a data or accessor property. If a trait property depends on mutable state, one should always "instantiate" such traits via 'maker' functions, to prevent a stateful trait from being composed multiple times with different objects:

// don't do:

var x = 5;

var StatefulTrait = Trait({

m: function() { return x; },

n: function(i) { x = i; }

});

// but rather:

var makeStatefulTrait(x) {

return Trait({

m: function() { return x },

n: function(i) { x = i; }

});

}In the case of StatefulTrait, if this trait is used to instantiate multiple objects, those objects will implicitly share the mutable variable x:

// bad: invoking o1.n(0) will cause o2.m() to return '0', implicit shared state

var o1 = Trait.create(Object.prototype, StatefulTrait);

var o2 = Trait.create(Object.prototype, StatefulTrait);In the case of makeStatefulTrait, that state can be made local to each trait instance if a new trait is created for each separate instantiation:

// good: invoking o1.n(0) will not affect the result of o2.m()

var o1 = Trait.create(Object.prototype, makeStatefulTrait(5));

var o2 = Trait.create(Object.prototype, makeStatefulTrait(5));This example code demonstrates how traits.js is used to build reusable "enumerable" and "comparable" abstractions as traits. It also shows how a concrete collection-like object (in this case an interval data type) can make use of such traits. For an in-depth discussion of how traits can be used to build a real Collections API, see [3].

The animationtrait example is a direct translation of the same example from [2], showcasing stateful traits.

The unit tests are a valuable resource for understanding the detailed semantics of the composition operators.

Because trait composition is essentially flattened out when a trait is instantiated into an object, method lookup of trait methods is confined only to the constructed object itself. There is no inheritance chain to traverse in order to look up trait methods.

The downside of trait composition by flattening is that the number of methods per object is larger. To reduce the memory footprint, an efficient implementation should share the property structure resulting from a trait instantiation between all objects instantiated from the same create callsite. That is, it should be able to construct a single vtable to be shared by all objects returned from a single create callsite.

While designing this library, great care has been taken to allow a Javascript engine to partially evaluate trait composition at "compile-time". In order for the partial evaluation scheme to work, programmers should use the library with some restrictions:

- The argument to

Traitshould be an object literal. - The first argument to

Trait.resolveshould be an object literal whose properties are either string literals or the literalundefined. - The arguments to all composition functions should be statically resolvable to a trait.

At first sight, these restrictions may look severe. However, recall that traits should be thought of more as classes than as objects: they are meant to describe the structure of objects, and the above constraints are trivially satisfied if you use traits as the declarative entities they are meant to be. Now, the cool thing about traits.js is that it does not preclude programmers from violating these restrictions, enabling programmers to easily write generic trait composition code, traits generated at runtime, etc. These traits won't be able to make use of optimized trait composition and instantiation, but that's a fair tradeoff to be made. It's like generating a Java class at runtime.

Partial evaluation would enable a smart implementation to transform the composition functions as follows:

Trait({ a: 1, ... }) // => literal-property-map

Trait.compose(Trait({ a: 1 }), Trait({ b: 2})) // => Trait({ a:1, b:2 })

Trait.resolve({ a: 'x' , ... } , Trait({ a: 1, b: 2, ... })) // => Trait({ a: Trait.required, x: 1, b:2, ... })

Trait.resolve({ a: undefined, ... }, Trait({ a: 1, b: 2, ...})) // => Trait({ b: 2, ... })

Trait.override(Trait({a: 1, b: 2}), Trait({ a: 3, b: 4, c: 5 })) // => Trait({ a: 1, b:2, c: 5})

Trait.create(proto, literal-property-map) // => native-create

Trait.object(object-literal) // => Trait.create(Object.prototype, Trait(object-literal))A literal-property-map is a property map defined as an object literal, with all of the required structural information available "at compile time". The key idea of the partial evaluation is that calls to Trait.create with a literal property map can be transformed into a fast native implementation of Trait.create, specialized for that property map. All objects generated by this native implementation can share the same v-table when they are created.

traits.js does not provide an operator to test whether an object was instantiated from a particular trait. In principle, traits are not meant to be used as a type/classification mechanism. This is better left to separate, orthogonal concepts such as interfaces.

If Javascript would at some point have the notion of interfaces or "brands" to classify objects, the API of the create function could be extended to allow for objects to be "branded" as follows:

var o = Trait.create(proto, trait, { implements: [ brand1, brand2, ... ] });Trait composers cannot make methods "inherited" from a trait private.

Required methods of a trait must, by design, be provided by other traits as part of their public interface, and thus also become part of the public interface of instantiated objects. If a trait really requires a method that ought to be private in the final composition, it can use lexical encapsulation to hide such required methods:

function makeTrait(privateRequiredFoo) {

return Trait({

m: function() { privateRequiredFoo() }

})

}

var t1 = makeTraitProvidingFoo();

var t2 = makeTrait(t1.foo);

var o = Trait.create(

Trait.compose(

Trait.resolve({foo: undefined},t1),

t2));

// foo is now a private method of the composition- [1] "Traits: Composable units of Behavior" (Scharli et al., ECOOP 2003) (paper): the original presentation of traits, including a deep discussion on the advantages of traits over mixins and multiple inheritance.

- [2] "Adding State and Visibility Control to Traits using Lexical Nesting" (Van Cutsem et. al, ECOOP 2009) (paper): describes a trait system in a lexically-scoped, object-based language similar in style to Javascript.

- [3] "Applying Traits to the Smalltalk Collection Classes" (Black et al., OOPSLA 2003) (paper): describes a concrete experiment in which traits were used to refactor the Smalltalk Collections hierarchy.

- [4] "Scheme with Classes, Mixins and Traits" (Flatt et al., APLAS 2006) (paper ): section 7, related work provides a very comprehensive discussion on the overloaded meaning of the words mixins and traits in various programming languages