Parquet-rewriter is a way to update parquet files by rewriting them in a more efficient manner. Parquet-rewriter accomplishes this by only serializing/deserializing dirty row groups (ones that contain upserts or deletes) and passing others through to the destination file in their raw, unmodified form. This can be significantly faster than rewriting your parquet file from scratch.

Historically Parquet files have been viewed as immutable, and for good reason. You incur significant costs for structuring, compressing and writing out a parquet file. It is better to append data via new parquet files rather than incur the cost of a complete rewrite. This works well with event based datasets where redundancy and duplicates can be tolerated. However, when you are dealing with transactional recordsets or aggregate data, then redundant or obsolete records can become a problem. Parquet-rewriter provides a potentially cheaper alternative to completely rewriting your parquet files whenever you need to update these types of recordsets.

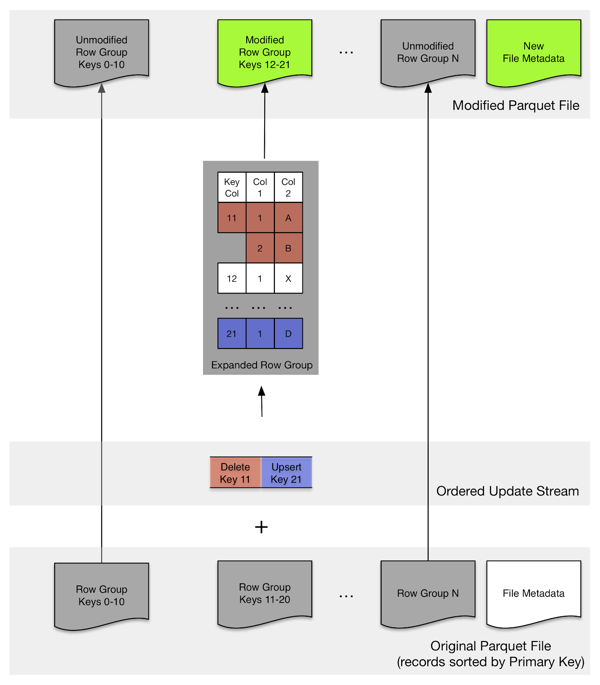

Parquet horizontally partitions sets of rows into row groups as depicted by this diagram:

Each row group is completely independent, and row group locations and statistics are stored at the trailing end of the file. parquet-rewriter takes advantage of these characteristics and its update strategy revolves around mutating only dirty row groups, ones that contain new, deleted or updated records, and passing through unmodified row groups in their raw and already compressed form.

parquet-rewriter makes the following assumptions: First, all rows in each parquet file / shard need to be sorted by a primary key column. Secondly, all updates need to be applied using the same sort order.

/*Let start out with a thrift structure of the type:

...

struct Person {

1: required string uuid,

2: required Name name,

3: optional i32 age,

4: Address address,

5: string info

}

// an update record can be either an upsert

// or a delete, in which case we just pass in the uuid

union Update {

// set person if you want an upsert

1: Person person,

// set uuid if you want a delete

2: string uuid

}

We are going to use uuid as our key field and the parquet records will be sorted and partitioned into N shards

Assuming you run an update in parallel, and for each shard you call an update function that takes an input

path and an output path

*/

void updateParquetFile(Configuration conf,Path sourceFile,ArrayList<Update> sortedUpdateRecords,Path destFile) {

// this maps Person object to uuid (the key field)

ParquetRewriter.KeyAccessor<Person,Binary> keyAccessor = (person) -> { return Binary.fromConstantByteArray(person.getUuid().getBytes()); };

// construct rewriter object

ParquetRewriter<Person,Binary> rewriter

= new ParquetRewriter<Person,Binary>(

conf,

sourceFile,

destFile,

new ThriftReadSupport<Person>(Person.class),

new ThriftWriteSupport<Person>(Person.class),

rowGroupSize,

keyAccessor,

ColumnPath.get("uuid"));

try {

// now walk updates ...

for (Update update : updates) {

// if this is an upsert ...

if (update.isSetPerson()) {

rewriter.appendRecord(update.getPerson());

}

else {

rewriter.deleteRecordByKey(

Binary.fromConstantByteArray(updates.getUuid().getBytes()));

}

}

}

finally {

rewriter.close();

}

}

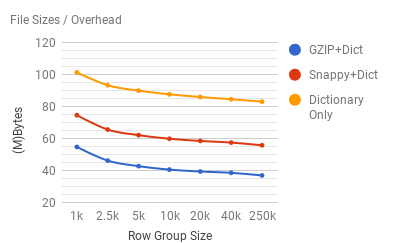

Generally speaking, the more row groups you end up mutating, the more costly your update becomes. So it is preferable to keep row groups sizes on the smaller side, but what is small and is there a penalty for too small a row group size ? Here is a graph of file sizes across two dimensions: row group size and compression type. This file consisted of 234000 records, each approximately 1800 bytes in size:

From the graph, we can see that, across all the compression schemes, there is a significant overhead associated with smaller row group sizes. However, this overhead becomes less significant as we approach approximately the 10k mark. At Factual, we use a 10K row group size.

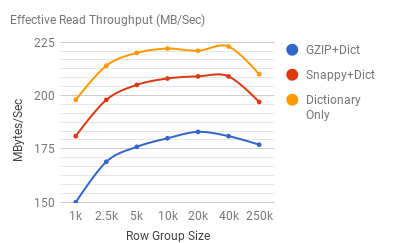

Next, lest look at effective read/write throughput at across the same dimensions:

We define effective throughput to be the amount of uncompressed raw data that is available for us to process every second. Read throughput seems to suffer significantly at the lower row group sizes, while write throughput numbers seem to suffer less from smaller sizes, perhaps due to the fact that other CPU bound tasks dominate most of the write workflow.

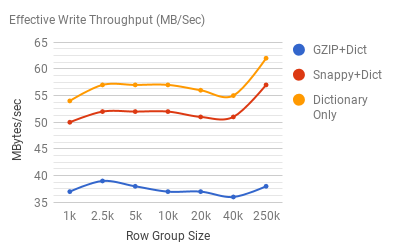

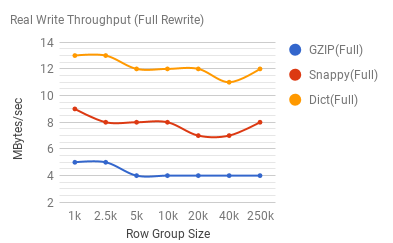

Lastly, lets look at real write throughput at 100% rewrite, vs. the 10%, and 50% rewrite thresholds respectively. Here are the numbers if we rewrite 100% of our file:

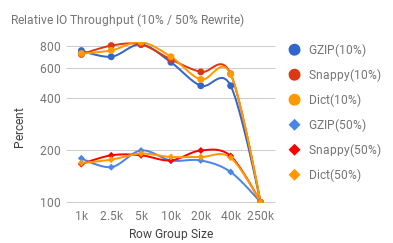

First of all, write throughput is pretty dismal, and obviously 100% CPU bound. Dictionary compression by itself is pretty expensive, and block compression (especially gzip) further degrades this performance. The following graph demonstrates the relative throughput increase for the 10% vs. 50% (row group) rewrite scenarios:

We see a siginificant performance boost when the updates are in 10% range, but even at 50% threshold, we have closed to doubled our IO throughput.