-

Notifications

You must be signed in to change notification settings - Fork 312

Introduction To GraphChi

GraphChi can process computation on very large graphs by using a novel Parallel Sliding Windows -algorithm. The graph is split into P shards, which each contain roughly the same number of edges in sorted order.

TODO: write better and link the paper.

This section describes the Parallel Sliding Windows (PSW) method (Algorithm 2). PSW can process a graph with mutable edge values efficiently from disk, with only a small number of non-sequential disk accesses, while supporting the asynchronous model of computation. PSW processes graphs in three stages: it 1) loads the graph from disk; 2) updates the vertices and edges; and 3) writes updated values to disk. These stages are explained in detail below, with a concrete example. We then present an extension to graphs that evolve over time, and analyze the I/O costs of the method.

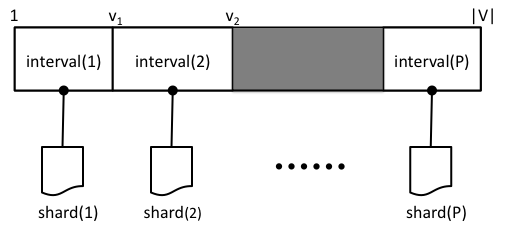

Under the PSW method, the vertices V of graph G = (V, E) are split into P disjoint intervals. For each interval, we associate a shard, which stores all the edges that have destination in the interval. Edges are stored in the order of their source.

Intervals are chosen to balance the number of edges in each shard; the number of intervals, P , is chosen so that any one shard can be loaded completely into memory. Similar data layout for sparse graphs was used previously, for example, to implement I/O efficient Pagerank and SpMV .

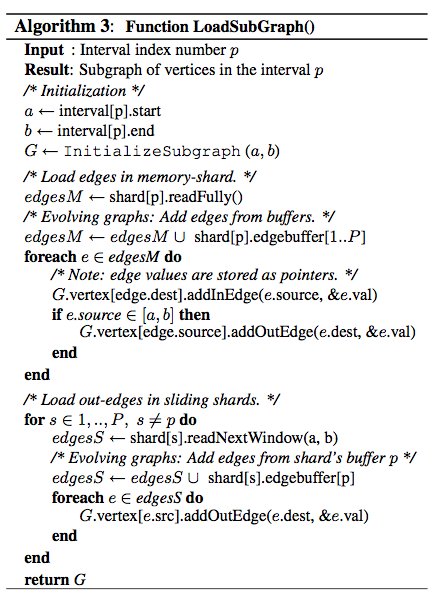

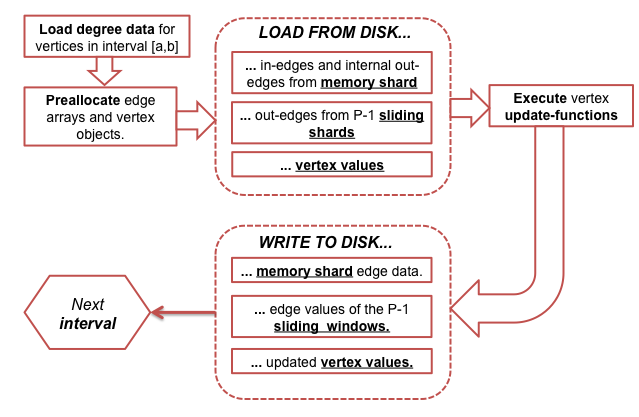

PSW does graph computation in execution intervals, by processing vertices one interval a time. To create subgraph of the vertices in interval p , edges (with their associated values) must be loaded from disk. First, Shard(p), which contains the in-edges for the vertices in interval(p), is loaded fully into memory. We call thus shard(p) the memory-shard. Second, because the edges are ordered by their source, the out-edges for the vertices are stored in consecutive chunks in the other shards, requiring additional P-1 block reads. Importantly, edges for interval(p+1) are stored immediately after the edges for interval(p). Intuitively, when PSW moves from an iteration to the next, it slides a window over each shard. We call the other shards the sliding shards. Note, that if the degree distribution of a graph is not uniform, the window length is variable. In total, PSW requires only P sequential disk reads to process each interval. A high-level illustration of the process is given in Figure , and the pseudo-code of the subgraph loading is provided in Algorithm 3.

After the subgraph for interval p has been fully loaded from disk, PSW executes the user-defined update-function for each vertex in parallel. As update-functions can modify the edge values, to prevent adjacent vertices from accessing edges concurrently (race conditions), we enforce external determinism, which guarantees that each execution of PSW produces exactly the same result. This guarantee is straight-forward to implement: vertices that have edges with both end-points in the same interval are flagged as critical, and are updated in sequential order. Non-critical vertices do not share edges with other vertices in the interval, and can be updated safely in parallel. Note, that the update of a critical vertex will observe changes in edges done by preceding updates, adhering to the asynchronous model of computation. This solution, of course, limits the amount of effective parallelism. For some algorithms, consistency is not critical (for example, see ), and we allow user to enable fully parallel updates.

Finally, the updated edge values need to be written to disk and be visible to the next execution interval. PSW can do this efficiently: The edges are loaded from disk in large blocks, which are cached in memory. When the subgraph for an interval is created, the edges are

referenced as pointers to the cached blocks. That is, modifications to edge values directly modify the data blocks themselves.

After finishing the updates for the execution interval, PSW writes the modified blocks back to disk, replacing

the old data. The memory-shard is completely rewritten, while only the active sliding window of each sliding shard

is rewritten to disk (see Algorithm \ref{alg:PSW}). When PSW moves to next interval, it reads the new values from disk, thus implementing the asynchronous model. The number of non-sequential disk writes for a execution interval is

We now describe a simple example, consisting of two execution intervals, based on Figure below. In this example, we have a graph of six vertices, which have been divided into three equal intervals: 1-2, 3-4, and 5-6.

Figure a shows the initial

contents of the three shards. PSW begins by executing interval 1, and loads the subgraph containing of edges drawn

in bold in the figure c. The first shard is the memory-shard, and it

is loaded fully. Memory-shard contains all in-edges for vertices 1 and 2, and a subset of the out-edges. Shards 2 and 3 are the sliding shards, and the windows

start from the beginning of the shards. Shard 2 contains two out-edges of vertices 1 and 2; shard 3 has only one.

Loaded blocks are shaded in Figure a.

After loading the graph into memory, PSW runs the update-function for vertices 1 and 2.

After executing the updates, the modified blocks are written to disk; updated values can be seen in Figure b.

PSW then moves to second interval, with vertices 3 and 4. Figure d shows the corresponding edges in bold, and Figure b shows the loaded blocks in shaded color. Now shard 2 is the memory-shard. For shard 3, we can see that the blocks for the second interval appear immediately after the blocks loaded in the first. Thus, PSW just "slides" a window forward in the shard.

Diagram below shows the GraphChi operation flow.

See separate page for Evolving-And-Streaming-Graphs.

Since version 0.2, GraphChi now stores the shards in 4-megabyte compressed blocks. This enables also DynamicEdgeData support. See more from GraphChi-Version0p2-Release.